Local residents along the northern rivers bordering Myanmar are now living in fear, concerned as much about the impacts from the transboundary toxic pollution caused by unregulated mining upstream in Myanmar as on their uncertain future

Golden rays of the afternoon sun penetrate the overcast sky in the late rainy season, spreading their glow over 59-year-old Thip Khamlue’s two-rai riverside field near the Kok River in Mai Mhok Jam village in the far northern district of Mai Ai, bordering Thailand’s Chiang Mai province and Myanmar’s Shan State.

Some of her “ladies” have been left strained under the sunlight as the field had been swamped by mud-laden floodwaters twice already during the past months. But Ms. Thip still considers herself somewhat lucky because she had managed to harvest some yield of this special species of Okra plants, the family’s main source of income.

It is the next growing season, this coming November, that she feels uncertain about.

“They said they would come to inspect the soil in my field before I grow the next crop to check if it had been affected by the toxic contamination in the river. My field is not next to the river; it’s farther than 30 metres, which they said is deemed safe. Hopefully, it will survive the toxic contamination spilling over from the river,” said Ms. Thip, her tone reflecting doubt.

The toxic pollution that is crossing the border into Thailand from Myanmar’s upstream areas as a result of unregulated mining is now causing anxiety and taking a psychological toll on the local residents downstream. (Read: SPECIAL REPORT: The Poisoned Rivers: From gold to rare earth, unregulated mining in Myanmar poisons the Mekong and its tributaries in Northern Thailand)

It’s not just Ms. Thip. Tens of thousands of farmers and residents in this bordering district and several more in Chiang Rai, where the Kok, Sai, Ruak and the Mekong Rivers pass through, share her concerns about the growing uncertainty in their lives. Water, food … they are no longer sure what is safe for consumption.

Since the issue broke out in March, these residents have been kept in the dark about the levels of toxic pollution and contamination. Scant and scattered information from state officials has not helped matters. In some areas, like Thaton, the residents are posing hard questions: they want to know if there has been a cover-up, especially regarding sensitive issues relating to their health.

“They (community-based health-promoting hospital) told us to wait for the test results, but I have not heard anything from them as to when I will know my test result or my sickness,” said Gob Kodkham, a 42-year-old resident of Thaton’s Kaeng Sai Mool patch village. His urine was sent for tests months after some rashes developed on his skin in April following his long hours in the water working on a bamboo raft for visitors during the Songkran festival to earn some money.

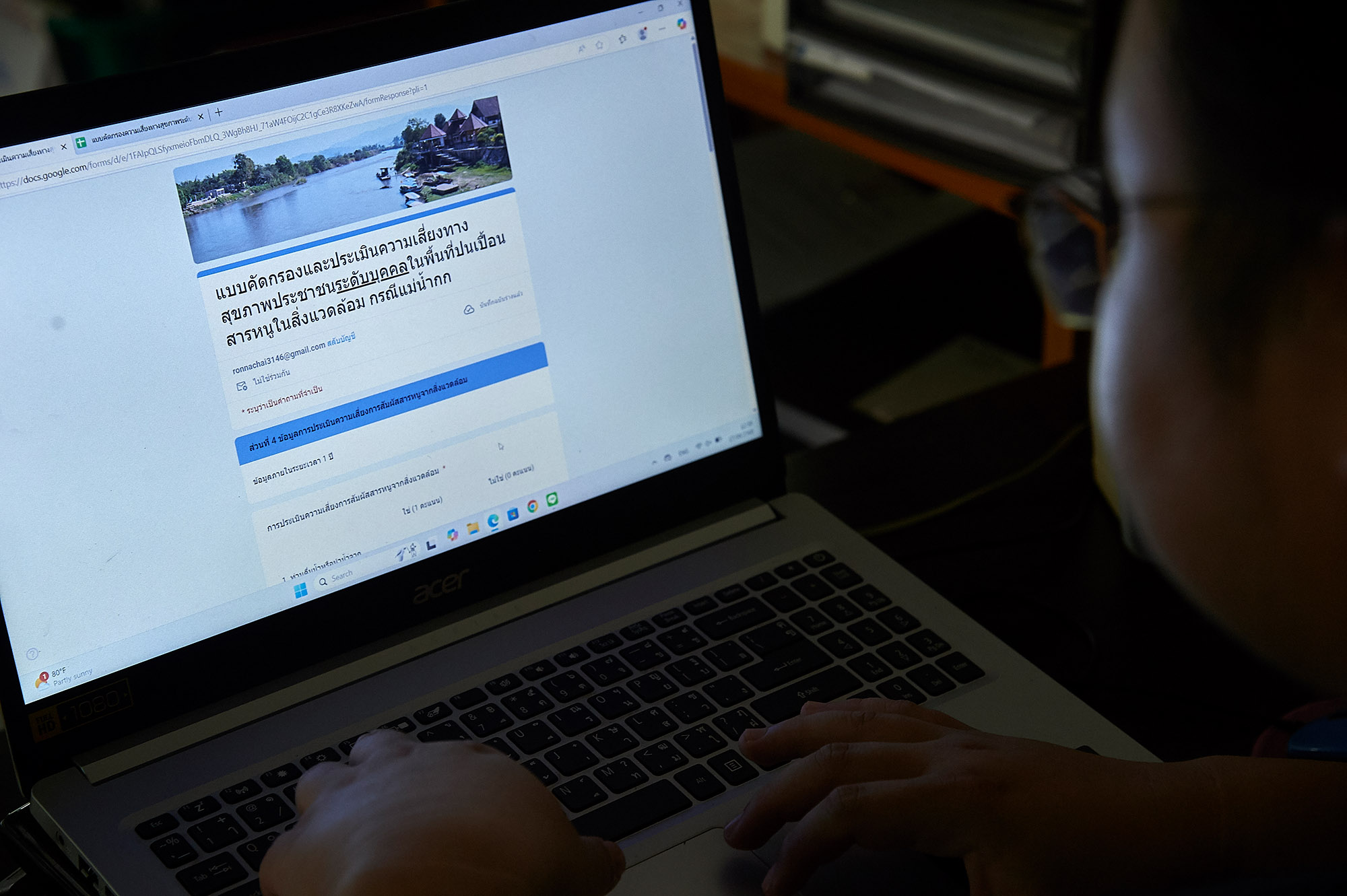

Shortly after the incident, local state officials, starting with those from the Pollution Control Department’s Environmental and Pollution Control Office 1 (Chiang Mai), began their investigation. They formed a team to conduct water testing along the 300-kilometre Kok River before expanding their testing to other rivers, including the Mekong.

Other local government agencies responsible for water consumption, fisheries, agricultural production, and public health, then followed as instructed by their main agencies and the government.

But according to some concerned local officials, their testing and monitoring plans are limited in scope as they are extensively tied up with the annual budget. Some of the work had to be integrated into their routine monitoring work, they said.

So their work is not quite as comprehensive and consistent as it is supposed to be, the officials admitted. For instance, the very first tests on fish and farm crops were conducted on only a few samples due to budget constraints.

In Chiang Mai province or on the Sai River in Chiang Rai, for example, the officials managed to set up just one location in each area for fishery sample collection, despite the fact that effective surveillance of toxic substances needs scientific planning and spans a long period of time — at least five 5 years for fishery — as it takes time for these substances to accumulate in aquatic animals and show effects.

So far, most of the officials’ testing and monitoring, except for those from the PCD’s Office 1, have shown similar results: no toxic substances were found, and if found, they were below the safe limits. It’s only recently that the test results on water for household consumption showed lead contamination in up to 18 villages along the Kok River. This was not disclosed to the public but was revealed by a Chiang Mai MP of the opposition People’s Party, Phattarapong Leelaphat, who has been following up on the issue with the government.

The results on health monitoring are far more complicated, as the results of large-scale testing in the two provinces during late July have not yet been disclosed to the public.

Some observers have noted that the data of the officials has not been aggregated and integrated to help form a dataset that is solid and comprehensive enough to help the government frame proper policies or devise solutions to this problem. And when it comes to information dissemination and communication with the public and affected residents, there are serious shortcomings as they are either scant, scattered or inaccessible.

Mr. Gob, who has been waiting for the test result on his health, remarked: “They hardly tell us anything — whether we are sick or what we have to do next? We are just left to worry and worry.”

But amid growing concerns and frustrations of the residents, impacts on the ground have started to be felt in several communities along the rivers.

The residents are now staying away from their rivers. There has hardly been any fishing in the rivers for months, while other activities have almost come to a halt, including tourism or even traditional events like Songkran celebrations.

And more critically, safe water and soil have become scarce, driving people to desperately search for the resources they can trust — to simply live.

Photo: Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Photo: Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Photo: Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Photo: Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Photo: Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Photo: Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Photo: Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Photo: Sayan Chuenudomsavad

A few fish samples, including alien sucker fish feeding on the riverbed, caught in the Sai River, can be seen before being sent to a lab for testing. Local fishery officials have put extensive efforts into collecting these live samples, as it’s not easy to collect them. This prompts the number of samples they find each time varies, they said. The officials also tried to set up as many locations as they could along the rivers: a total of 21 locations so far — 20 in Chiang Rai, and only one in Chiang Mai. To monitor toxic substances in aquatic animals takes time, and it needs systematic planning and adequate budget, both of which are currently absent from the government’s plans and policies, the officials said. The test results so far have not shown toxic contamination beyond the acceptable standard, but fishery officials in responsible areas tend to inform the residents not to consume fish from those rivers.

Photo: Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Photo: Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Since the issue broke out in March, the impacts have been felt by local residents as their livelihoods and occupations have been affected. Karen Ruammitre village, a popular eco-tourism village by the Kok River in Mae Yao subdistrict in Chiang Rai province, has been affected by a lack of visitors who used to come to see the elephants. Mahouts are struggling to take care of their giant animals, as they too are unsure whether the food and water they provide their elephants are safe. They have already decided to stop bathing their elephants in the river for fear they could be sickened by the toxic water. They have invested in building an artificial tank and a tap water system connected to water sources on the mountains further away to ensure that their animals will have safe water to drink and bathe.

Photo: Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Photo: Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Photo: Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Photo: Sayan Chuenudomsavad

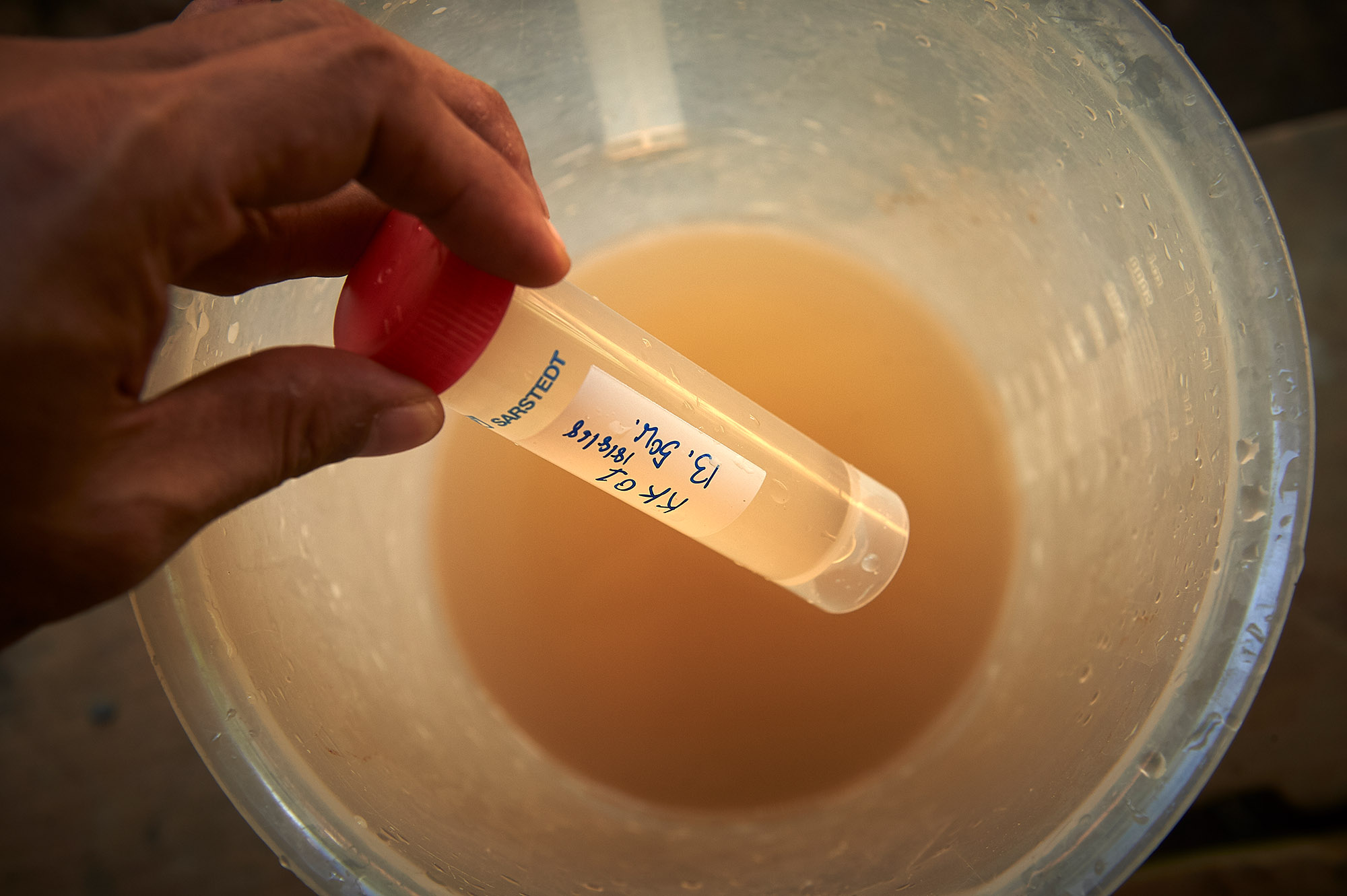

A water sample from KK01 near the Thai-Myanmar border.

Photo: Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Photo: Sayan Chuenudomsavad

This photo essay is part of the SPECIAL REPORT SERIES: Environmental Challenges under the Great Power’s Influences.