Unregulated mining in Myanmar is proliferating unabated. It’s now poisoning the Mekong and its tributaries, including the lifelines of local residents in the North — the Kok and Sai-Ruak rivers — without anyone knowing how to address this transboundary toxic pollution that is driven by global demands for noble minerals far away

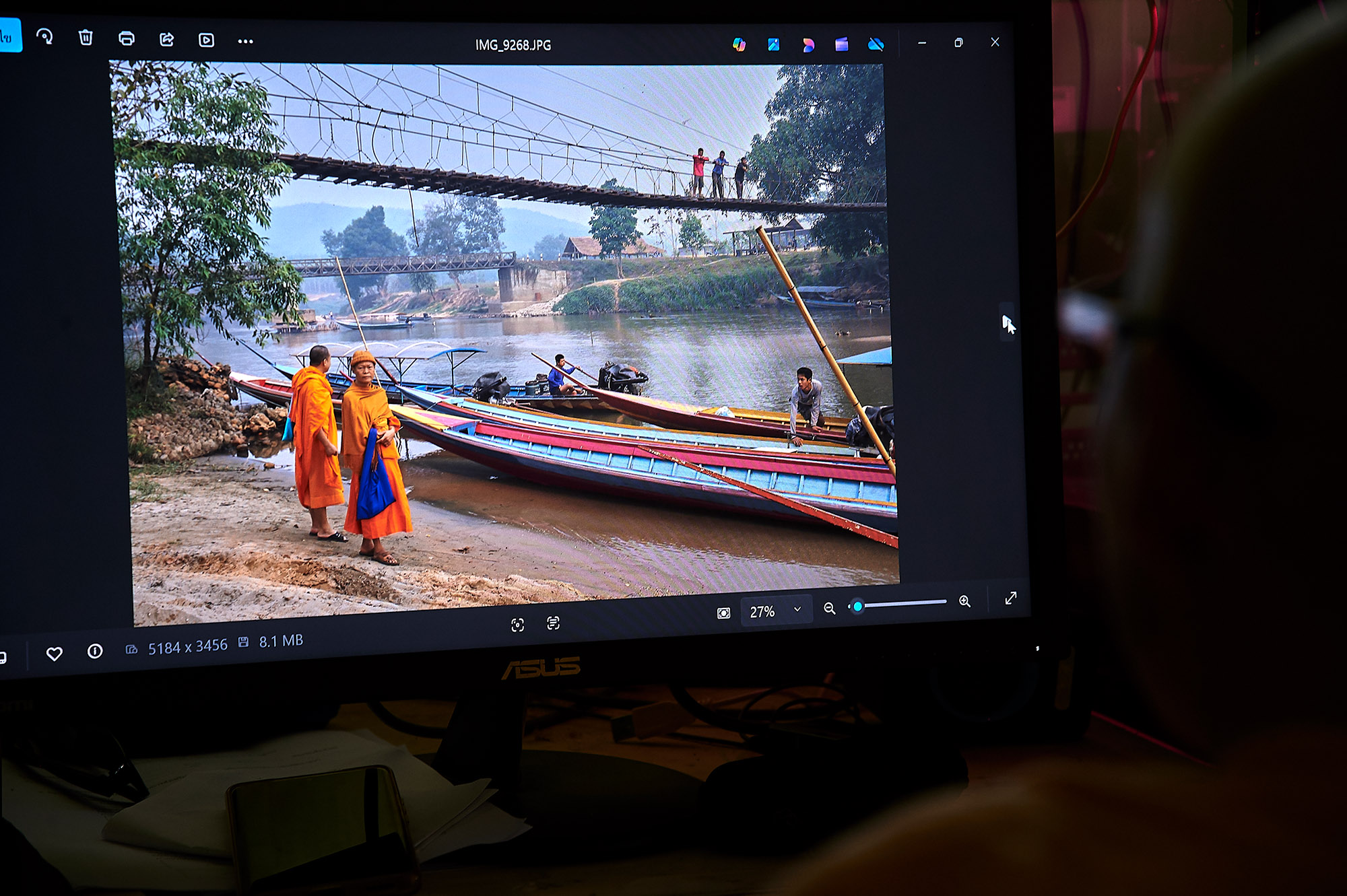

Revered Buddhist monk Phra Maha Nikhom once fought against his motherland because it had not recognised his citizenship in the first place. Given that the Thaton subdistrict in Chiang Mai’s Mae Ai district, where he was born and grew up, borders Myanmar, native residents from various ethnic groups there were often mistaken for citizens of the neighbouring country.

In his 61 years, the abbot of Phawana Nimitra Temple in Thaton has become a fighter again — this time to save the motherland he once fought against. What he is up against this time is the transboundary toxic pollution and unregulated mining in Myanmar’s upstream areas of the transboundary Kok River.

“Living in a border town like this, I have been through a lot of challenges and know the problems here well. But they have taught me one thing: Don’t lose hope. We must even initiate it by ourselves and carry on, even if no one is with us.

“People who have been fighting this problem with me say they feel desperate and have lost hope. So I told them: Once you have lost hope, you will lose, and you will lose today,” said the abbot and spiritual leader of the Thaton community.

Photo: Sayan Chuenudomsavad

The abbot, who belongs to the “Tai Yai” ethnic group, still has vivid memories of his childhood as a novice monk when he had to follow the path of non-violence, or Ahimsa, to gain Thai citizenship. Because Thaton was just a patch-border village, remote from the centre of power, the native residents there did not bother to develop a sense of identity beyond making a living.

They had always made a living as far as 30 kilometres upstream near Mong (Mueang) Yawn in Myanmar’s Shan State, where mostly “Tai” and “Lahu” populations lived, growing rice, vegetables and other farm products.

Phra Maha Nikhom said people on both sides had socialised and sustained their relationship for years. The relationship became strained due to changes in demography and land use up there.

As a kid, the senior monk still remembers travelling upstream with his parents to grow rice and vegetables on their two-rai (0.32 hectares) plot of land. People from Thaton tended to build makeshift shelters to stay for weeks or months to watch over their farm products, and over time, their structures turned into a sort of patch village up there.

“People here walked up and down the mountains as if they lived on both sides of the country. In fact, we grew rice and vegetables on land to which there were overlapping claims. And then the Wa and their armed group moved down to Mong Yawn. The land there was taken over and eventually integrated as part of Myanmar. This happened just within the last 20 to 30 years,” said the senior monk.

Photo: Sayan Chuenudomsavad

As more new faces came and there was instability in the area, Thaton residents decided to permanently move down from the mountains — only to find out that they were mistaken and treated as “stateless” people. District officials later issued immigrant cards for them or enforced deportation if they refused to accept those items, Phra Maha Nikhom said.

According to the Hill Area and Community Development Foundation, run by former senator Tuenjai Deetes, more than 1,440 residents in the district, as recorded in the early 2000s, had a problem with their nationality. The senator was among the political figures who helped push for solutions for these people. Among them was Phra Maha Nikhom himself.

It took Phra Maha Nikhom more than 10 years to fight for his identity as a resident of Thaton, and therefore a Thai national. He had to travel back and forth between remote Thaton, Mae Ai in Chiang Mai, and as far as Bangkok over those painful years to prove and verify that he was a Thai citizen. It was not until he reached his 30s that he finally gained his first identification card and his Thai nationality.

By then, his family’s inherited land upstream became a part of Myanmar and was exploited by both the Burmese government and the Wa armed group, Phra Maha Nikhom recalled. The monk said land use upstream had changed dramatically during the last 20 to 30 years, mainly following the mass immigration of the Wa.

Photo: Sayan Chuenudomsavad

A vast tract of forests there and the Kok watershed in Mong Kok further from Mong Yawn were turned into concessionary plots for logging. And as trees were cut down and forests were cleared, the land was later turned into rubber plantations.

To grow rubber, planters needed to use a massive amount of farm chemicals. The chemicals were then simply flushed down the hills and flowed into the Kok River. Phra Maha Nikhon said this was the first time people in Thaton had experienced toxic pollution from upstream areas, as they felt itching or developed rashes after coming into contact with the river water.

Casinos and call centres then popped up there. However, as China seriously suppressed the activities, mining began to replace those businesses and has since been proliferating in the area over the past three to four years. It has reached a point where Phra Maha Nilkhom believes he could no longer sit still in his temple but had to take up cudgels again — this time to save Thaton and beyond.

In March this year, he led Thaton residents to march for the first time in a campaign against the mining activities upstream. It has become the first civil society movement to raise public awareness about the issue and has also gained momentum elsewhere, including Chiang Rai province further downstream.

The issue has since evolved into a regional and international challenge that is now testing not only the Thai government but also related administrations, including Myanmar and China.

“I used to travel as a pilgrim up to the Kok watershed in Mong Kok, around 150 kilometres away from our community, and have witnessed all these changes, but don’t travel any more these days due to insecurity in the areas. The land has changed, so have the people we used to deal with.

“But, as I said, don’t lose hope. Whatever hardship you are facing, if you think that it’s your fight, just do what you need to do — keep fighting,” said the abbot, who has been travelling here and there again to raise public awareness and understanding about the issue with his spiritual teachings of Dharma.

Photo: Sayan Chuenudomsavad.

The toxic metals

Phra Maha Nikhom did not know in the first place that he and his people were fighting an uphill battle. It is the heavy metals that are highly toxic and hazardous to people’s health, generated from unclear and various sources on land without clear autonomy or even outlawed, by people with unclear accountability and responsibility, and for minerals that are highly coveted by the world’s major powers.

In short, people involved in this issue so far have had no clear idea who they should talk to for help in addressing the issue and ending the toxic pollution.

Following the monk’s campaign and complaints about the impact on public health, including skin rashes among children in Thaton who swam in the river, which became heavily mud-laden throughout the year, the Pollution Control Department’s Environmental and Pollution Control Office 1 (Chiang Mai) was assigned to test the water and examine water quality for possible toxic contamination in the river.

According to Piyanoot Suangkham, the director of the Water Quality, Air and Noise Management Division at Office 1, the testing was unprecedented. She said the office had never conducted such extensive testing before. In the past, the PCD routinely checked the water quality of the Kok River and eight other heavy metals used as parameters four times a year from four locations designated in the river section downstream in Chiang Rai province.

The Kok River in Thailand runs through Chiang Mai’s Thaton and Mae Na Wang districts and Chiang Rai province before flowing into the Mekong River in Chiang Rai’s Chiang Saen district, running a distance of nearly 300 km in total. Its farthest upstream section is near the Thai-Myanmar border in Thaton.

According to the department’s records from the past 10 years, the PCD first detected Arsenic (As) beyond the permissible level at a final location near the Mekong River in Chiang Rai in 2023–2024, measured at 0.025 and 0.044 milligrams per litre (mg/L). The heavy metal was not among the eight heavy metal parameters.

The standard, which is the maximum acceptable concentration of arsenic in drinking water set by the World Health Organization (WHO), is 0.01 mg/L, or 10 micrograms per litre (μg/L), meaning the arsenic detected by the PCD exceeded the WHO’s guideline by more than one to three times.

According to the WHO, arsenic is naturally present at high levels in the groundwater of several countries as it’s a natural component of the earth’s crust. It is highly toxic in its inorganic form, or without oxygen, and contaminated water with arsenic for drinking, food preparation and irrigation, poses the greatest threat to public health, the WHO noted.

The WHO further noted that long-term exposure to arsenic from drinking water and food can cause cancer and skin lesions. It has also been associated with cardiovascular disease and diabetes. In addition, the world’s public health organisation said that in utero and early childhood exposure have been linked to negative impacts on cognitive development and increased deaths in young adults.

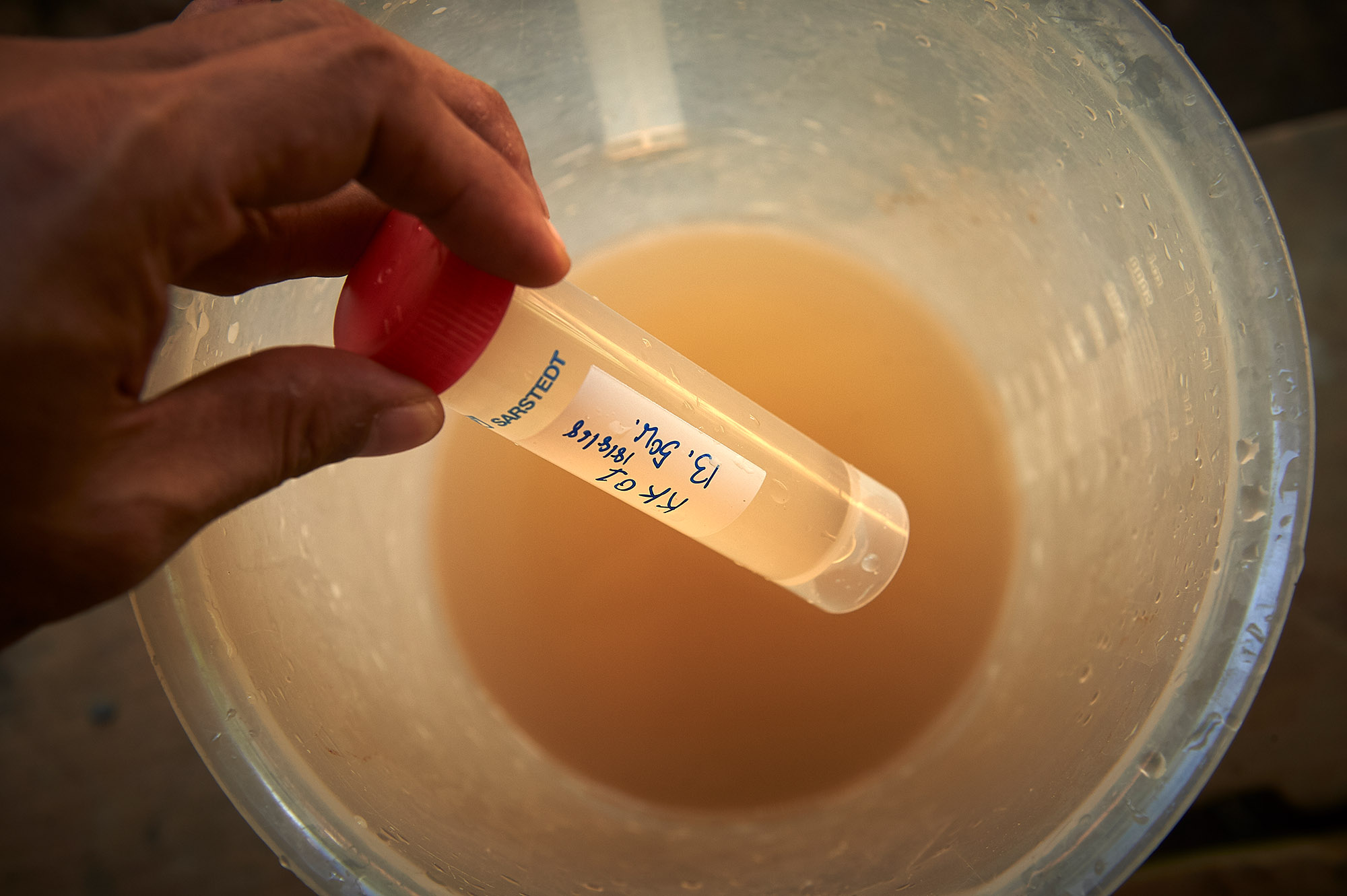

To examine the water quality this year to prove the facts, Ms. Piyanoot set up a team, focusing first on three new locations in Chiang Mai’s river section. The team then extended its testing to cover the whole river section, stretching from Chiang Mai’s Thaton to Chiang Rai’s Chiang Saen district. Altogether, 15 locations were designated along the river section in Thailand. The farthest location was set up near the Thai-Myanmar border in Thaton, only 600 metres away from it. It’s named KK01.

The team added four more locations on four tributaries of the Kok River to compare the results as they originate from watersheds within the country. It also expanded the testing to other rivers, which also have watersheds in Myanmar, designating eight more locations along the Sai and Ruak rivers and the Mekong, where they also flow into.

Since late March, 27 locations designated on those rivers and tributaries have been visited twice a month by the team to collect water samples and once a month for sediment samples.

Photos: Sayan Chuenudomsavad

The earliest results from the first and second tests conducted in late March and April showed that arsenic in the water at the first location of the Kok River near the border was beyond the standard, being measured at 0.026 and 0.037 mg/L, respectively.

The heavy metal in sediments was also found to have exceeded the standard in all three locations of Chiang Mai’s river section and some other locations downstream in Chiang Rai, showing up at 20 to 33 mg/kg. The standards are set at no more than 10 mg/kg, deemed safe for aquatic animals, and at 33 mg/kg, considered as harmful to both aquatic animals and humans.

Besides, Lead (Pb), which is among the eight heavy metal parameters, was also found in the water at the first location of the Kok River in the first testing — 0.076 mg/L — and therefore exceeding the standard set at 0.05 mg/L.

In the Sai and Mekong rivers, arsenic was also high in the second testing. All three locations in the Sai River detected arsenic between 0.044–0.049 mg/L, while two locations in the Mekong detected arsenic between 0.031–0.036 mg/L. Lead was also detected in the Sai River in the second testing — 0.058–0.066 mg/L at all three locations.

In the fourth test for water quality and the third test for sediment quality conducted late May, arsenic in water and sediments on the riverbed were found to have exceeded the standard at all 23 locations in all key rivers for the first time, suggesting widespread contamination along the rivers.

Besides, the team started to detect lead in sediments on the bed of the Kok River in at least three locations, and its level exceeded the minimum standard of 10 mg/kg. It also detected Manganese (Mn) in the water in the Sai River for the first time, which was measured between 1.10–1.30 mg/L, while the standard is at 1.00 mg/L.

The eighth water-quality testing conducted in July detected unusual levels of lead in the Kok, Sai and Ruak rivers. The levels of lead recorded in the Sai River were more than double the standard for the first time, ranging from 0.094 to 0.124 mg/L, while manganese was detected once again alongside it.

Ms. Piyanoot shared her observations based on the findings that arsenic levels tended to be high near the border and declined farther away. Combined with satellite images and information shared among Thaton residents, the team suspected that mining upstream was likely responsible for the toxic contamination of these heavy metals downstream, although they could not specify the types of mines up there.

Ms. Piyanoot also said the recent testing detected high levels of lead and manganese, suggesting there may be new types of mines operating in the areas. At this point, her team could not project the trend of the contamination, as external factors like rainfall and flooding could affect the presence of these heavy metals. The team needed more time to monitor them, Ms. Piyanoot said.

“These heavy metals come with sediments, so their presence varied depending on factors like rainfall and flooding. We cannot tell yet whether they have increased and whether the situation has worsened, but what we can say is these toxic substances are now present in our rivers and sediments, and they keep coming down,” said Ms. Piyanoot.

Photo: Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Asst. Prof. Dr. Sitang Pilailar of Kasetsart University’s Faculty of Engineering, who was a member of the government-appointed panel to look into the impacts of a large gold mine on nearby water sources in Phichit province, revealed to Bangkok Tribune that the panel had discovered heavy metals such as arsenic, lead and manganese beyond the standard in water sources near the mine, similar to those detected in the rivers in the North.

In addition, the panel also found Mercury (Hg) and Cadmium (Cd). These two substances are listed among the eight heavy metal parameters, but Ms. Piyanoot’s team has not yet found them exceeding permissible standards.

The occurrence of some of these heavy metals in the rivers in the North, therefore, could suggest that they were from gold mines upstream, Dr. Sitang said. However, she said they could also possibly come from rare earth mines, and this needs further investigation.

Through mining processes, these heavy metals may not be discharged directly from the processes themselves, but indirectly stirred up and released from the Earth as they are its natural components, she said.

So far, the recent testing by an academic from Mae Jo University has shown the presence of palladium in fish from one of those rivers. It’s a noble metal in the Earth’s crust that may have been involved with rare earth mining, the professor said. This, she added, needs further investigation to help identify the mines upstream.

Dr. Sitang said the gathering of information and the building of a body of knowledge for this issue at present are weak, as they are insufficient and not comprehensive enough to help guide proper solutions and policies.

For instance, the PCD’s testing cannot differentiate the types of arsenic in the rivers despite the fact that they are various and capable of transforming from non-hazardous to hazardous forms depending on the degree of oxygen they take in.

When the government came up with the idea to build a series of consecutive dams in the rivers to intercept the sediments and those heavy metals, especially arsenic, it was apparent that it did not know enough about the substances and their natures.

The dams, Dr. Sitang said, are aimed at intercepting the sediments and those heavy metals. But arsenic alone, once it precipitates on the riverbed, will turn into a hazardous form instead, as it lacks oxygen.

“It’s like we are solving the problem without knowledge. As long as we don’t know enough about it, we can never come up with proper solutions.

“So far, I have not seen that we are using knowledge, especially science, to help solve this problem despite the fact that it’s scientific. As long as we don’t know about these substances and their origins — where they were from or which mines disposed them of downstream, and so on, we will never be able to solve this problem.

“The point is I’m just talking about arsenic alone. We’re not talking about several other heavy metals, plus their interactions, and not to mention the contamination of these heavy metals in food chains and so on. One method may work well with one heavy metal, but not with the others. So what would you do next if your method fails?

“First, we need to know this problem much more than we know now, so that we can come up with proper solutions to deal with it,” said Dr. Sitang.

Photo: Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Gold or Rare Earth?

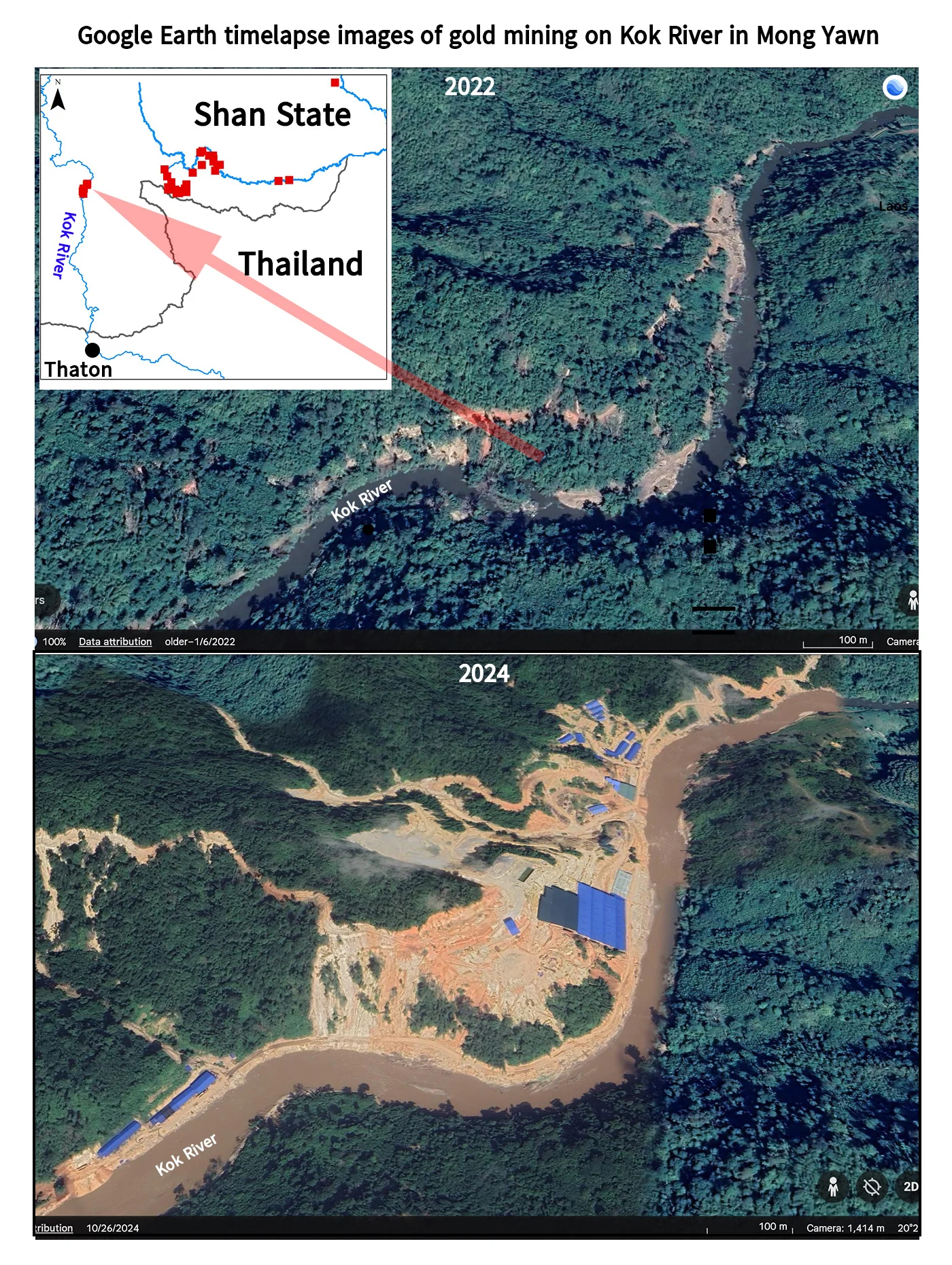

In mid-March, the Shan Human Rights Foundation, which has been promoting human rights in Shan State since 1990, revealed some facts about gold mining upstream in Mong Yawn in an area it said is controlled by the United Wa State Army (UWSA).

The organisation said that since 2023, large-scale gold mining has been taking place along the Kok River in Mong Yawn. However, the number of mines was not provided. The organisation claimed that the mining exacerbated the damage from the heavy flooding of the Kok River in September last year, citing that the Shan village of Peng Kham in Mong Yawn tract was entirely submerged with mud-laden floodwater. The organisation also believed that this was also the reason why Thaton and other villages along the Kok River downstream were also badly affected.

When making these revelations in March, the organisation said that gold mining in Mong Yawn had expanded a few months before. It claimed that according to information shared by some locals, mining operations took place 24 hours a day with more than 300 workers, mostly Chinese, and some Chinese companies running the business.

The organisation said the locals there were too afraid to use the water for domestic consumption, and there were few fish left in the river as the mining residue, including toxic gold extraction chemicals such as cyanide, directly contaminated the river.

The Geo-Informatics and Space Technology Development Agency later examined the opening of the soil surface upstream in Myanmar using satellite images and identified activity at several locations. One image was similar to what the foundation showed, but it did not indicate how many mines were up there.

Its findings were also presented to the Land, Natural Resources, and Environment Standing Committee of Thailand’s House of Representatives, which initiated a probe into the case.

A few months later, the foundation revealed again the mining activities near the old sites that were claimed to be gold mining. This time, they were apparently involved with rare earth, as the foundation compared the structures from satellite images with some rare earth mines in Kachin State.

Two of them were located within 25 kilometres of the Thai-Myanmar border above Thaton. The organisation claimed that the two rare earth mines were developed in mid-2023 and mid-2024, based on the historical satellite images.

“The damage to the environment and health of communities living near the rare earth mines in Kachin State is already well documented. The underground leaching has caused land collapse and poisoned ground and surface water, killing fish and wildlife and contaminating crops.

“The rare earth mines in Mong Yawn are likely already releasing harmful substances into the Kok River, worsening the existing contamination from gold mining, which is threatening the health of communities living along the river in southern Shan State and northern Thailand,” the foundation remarked..

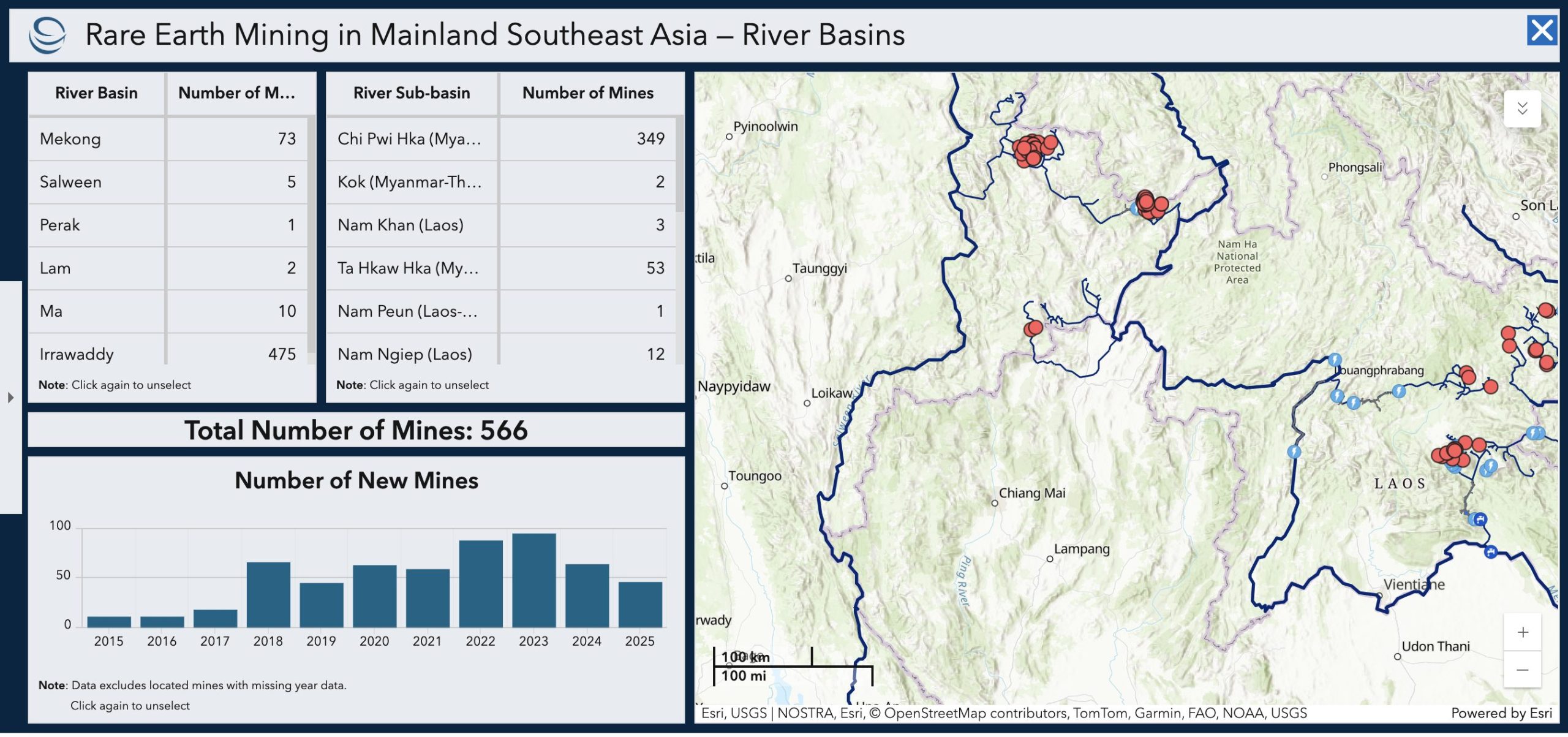

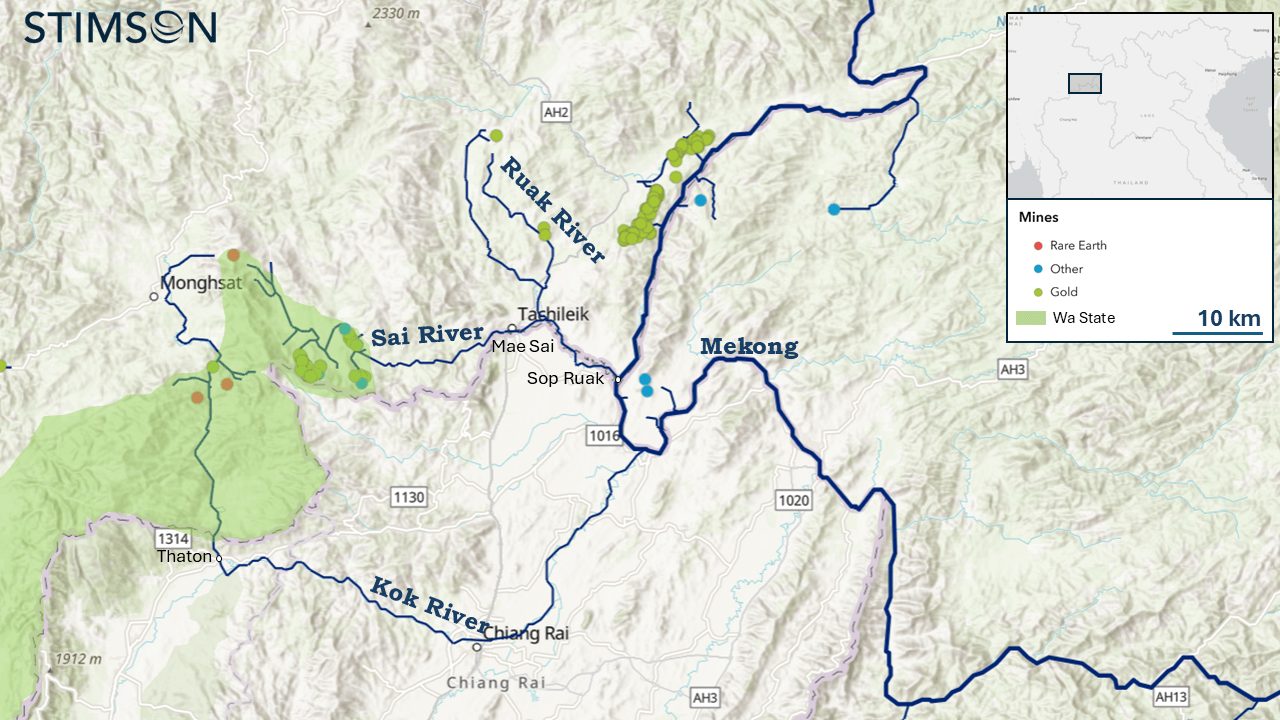

The US-based Stimson Center, promoting international security through research and policy, has gathered information and verified facts on the ground, including those from the foundation, using its advanced satellite technology and labs. The new project on visualisation and analysis of mining in mainland Southeast Asia will also look into the whole Mekong basin and share the information with the public here, starting with the rare earth mines recently released a few weeks ago.

Courtesy of ©Stimson Center

According to Stimson, unregulated rare-earth mining started in Myanmar’s portion of the basin and then expanded into Laos. The activity has ticked up significantly in the last four years.

The director of the Southeast Asia Program and the Energy, Water, and Sustainability Program, Brian Eyler, who is leading the new project, has used high-resolution satellite imagery from “Planet Labs” and managed to identify and verify 60 rare earth mines on the Myanmar side.

On the Nam Lwe (Nam Loi) River in Wa State, a 200-kilometre-long tributary of the Mekong, the highest concentration of rare earth mining has been recorded: 31 rare earth mines in Wa State near the Nam Lwe headwaters, and 26 mines in the National Democratic Alliance Army (NDAA, or Mong La Army) territory farther downstream.

The river flows into the Mekong at Sob Lwe on the Myanmar-Lao border, about 150 kilometres upstream from Chiang Rai.

According to the Shan Human Rights Foundation, which earlier investigated the activity in the area, it said other kinds of mining were also taking place along the Lwe River, including manganese mines.

In 2006, the foundation said the Lahu National Development Organisation had exposed how manganese mining in this area had harmed the environment and the health of two nearby hill villages inhabited by indigenous En and Loila peoples. Over 1,000 Chinese mine workers reportedly worked there.

The foundation also noted that over the past 20 years, manganese mining has expanded in this area dramatically, with runoff draining southward into the Lwe River.

Stimson’s satellite imagery also reveals a stunning fact that confirms the discovery of the foundation on the Kok River. Mr. Eyler’s team has found that three rare earth mines are active upstream of the Kok River, and at least two of them are possibly under development.

On the Sai and Ruak rivers, the team has found one active rare earth mine in the headwaters of the Sai River. It has also found at least nine gold mines, which are also active, and five more in development along the river.

In Laos, the team has found 15 rare earth mines on Mekong tributaries: three on the Nam Khan and 12 on the Nam Ngiep. Additionally, 12 more mines are detected in an adjacent basin: two mines on the Song Ma system, eight on the Song Chu system, and two on the Song Lam system. Mr. Eyler’s team was told by its source that entire communities situated downstream of the mines in Houaphan province cannot use river water for daily needs or fishing. These rivers in Houaphan are not in the Mekong Basin but rather flow into Vietnam’s central provinces.

“The most downstream of rare earth mines situated on the Nam Ngiep River in central Laos empties into the Mekong Mainstream just over 300 kilometres upstream from Cambodia. And mining activity other than rare earths is beginning to show up along rivers in southern Laos, even closer to Cambodia.

“This suggests Cambodia’s mainstream and possibly the Tonle Sap Lake, which, when combined, are responsible for producing 70% of the animal protein intake of the Cambodian population, are already experiencing levels of contamination,” Mr. Eyler remarked sharply on the possible impact on the so-called “Mekong’s womb”.

Courtesy of ©Transborder News

The Great Power’s push

According to records from noted organisations, including the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), Myanmar is the world’s major producer of mineral commodities and has been extensively engaged in the mining business with China, particularly in rare earths. The minerals are 17 metallic elements unique in their physical, chemical, and magnetic properties, and therefore much needed worldwide for modern technologies, from electric and hybrid vehicles and renewable energy sources like wind turbines and solar panels to medical equipment and military and defence applications.

In the agency’s 2020–2021 Minerals Yearbook (Burma) released in May last year, it noted that in 2020, before the coup, “Burma” was already the third biggest producer of rare earths in the world, accounting for 13% of world production; the third biggest producer of tin, accounting for 11% of world production and 14% of world reserves; and the 11th-biggest producer of manganese, accounting for 1.3% of world production.

The country also produces other mineral commodities, including cement, coal, copper, ferroalloys, fluorspar, jade, lead, natural gas, nickel, nitrogen, crude and refined petroleum, steel, sulfur, tungsten and zinc, according to the agency.

The USGS noted that production of rare earths in Burma increased from an estimated 29,000 tonnes in 2019 to an estimated 35,500 tonnes in 2020 (22%). And it was China that had imported all the rare-earth compounds (both unspecified rare-earth oxide and mixed rare-earth carbonate) produced in Burma during the year. Burma’s exports accounted for 74.4% of China’s total rare-earth compounds imports and approximately 50% of its feedstock of heavy rare earths, the agency noted.

In 2021, the agency estimated that the production was somewhere around 34,700 tonnes, and China’s imports accounted for 75.6% of its total imports in terms of quantity, compared with 74.4% in 2020 and 70% in 2019.

“Since the February coup (in 2021), approximately 100 rare earth mines started new activities in Chipwe, Pangwa, and Zam Nau in northern Kachin State on the Chinese border because the area was remote, not seriously affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, and controlled by junta-linked militia, and thus was not significantly affected by the coup,” the USGS noted on the new trend of rare-earth production that is also happening now in areas under the control of several non-state armed groups and organisations in Myanmar.

Global Witness, a non-profit human rights advocacy through investigations and policy recommendations, released in May last year its latest investigation of the rare earth production in Myanmar. It confirmed the proliferation of rare earth production in areas under these armed groups, especially in Kachin State.

According to Global Witness, which cited data from China’s General Administration of Customs, China’s imports of heavy rare earth oxides alone from Myanmar skyrocketed from their previous highs in 2021 to 41,700 tonnes in 2023. This was more than double China’s own quota for domestic heavy rare earth elements (HREE) mining, the organisation said.

“Since 2021, extraction has continued in the context of a ruthless dictatorship and widening civil conflict. The vast majority of the country’s extraction is explicitly illegal – controlled by an illegitimate military-aligned militia which, according to Kachin sources, has no regulation on mining standards,” said Global Witness.

The production there has set another new destructive trend, as depleted or degraded old mines were abandoned with traces of environmental destruction left behind, while mine operators just keep moving to new plots of land for new mines.

Mining sites in Kachin Special Region 1 in 2021 and 2023 (left to right) and in Momauk Township (below) in 2021 and 2023, detected by Global Witness.

Courtesy of ©Global Witness

According to Global Witness, most of the heavy rare earth elements from Myanmar originate from this state. Its investigation shows the shift of such a trend between areas under the control of different armed groups and organisations.

Satellite imagery showed that the number of rare earth mining sites in the Kachin Special Region 1, controlled by the militias aligned with Myanmar’s military rulers, had increased between 2021 to 2023 by more than 40%, numbering over 300 sites, the organisation said. (The number is 357 sites, according to the Institute for Strategy and Policy – Myanmar (ISP – Myanmar))

This has “saturated” the landscape around the border town of Pangwa, and as the town reaches its limits, new parts of Kachin State are coming under threat, the organisation noted.

A hundred miles southward, the satellite imagery also showed that rare earth mines were rapidly proliferating in Momauk Township, controlled by another armed organisation, the Kachin Independence Organisation (KIO). In 2021, the region had just nine mining sites, but by the end of 2023, the number had increased to more than 40, the investigative organisation noted.

Meanwhile, a massive amount of chemicals used in the mining processes were from China. In China, the technique called in-situ leaching — the injection of water mixed with chemicals into the Earth to leach out minerals before draining the slurry into the pools to scoop up minerals — has been widely reported to have polluted watercourses and farmland in the country.

Although it is still permitted in China, it is now governed by an official production quota and a strict set of standards and an environmental impact assessment. No such regulations apply in Myanmar, Global Witness noted.

According to the trade data cited by the organisation, up to 1.5 million tonnes of ammonium sulphate were exported from China to Myanmar in 2023, and this was up from 93,000 tonnes in 2015. The other chemical, oxalic acid, which is used for treating the rare earths once they’ve been drained from the mountainside, was also exponentially imported to Myanmar, from 342 tonnes in 2015 to 174,000 tonnes in 2023.

In contrast to the proliferation of the business, Kachin State has been left with a trail of environmental destruction, as documented in some photos of abandoned mines by Global Witness. The recent water sampling data cited by the organisation also showed that several streams in Kachin Special Region 1 were highly acidic and contained elevated levels of arsenic.

Meanwhile, workers interviewed by the organisation complained of various conditions ranging from coughing, numbness, skin conditions and kidney issues — all suggesting health risks from the chemical cocktail used in the mines, the organisation noted.

Courtesy of ©Global Witness

No one at this point can confirm whether the proliferation of rare earth mines in the Wa and Shan States, as verified and documented by Stimson Center, is replicating the mining in Kachin State, but environmental as well as health risks and impacts have started to be felt by a number of people living downstream, including those in Thaton and afar.

The value of Myanmar’s trade of the rare earths, meanwhile, is reported to have jumped to US$3.6 billion during the post-coup period from 2021 to 2024, according to ISP – Myanmar. This accounts for 84% of the total value recorded in the eight years from 2017 to 2024, the organisation noted. The peak year was 2023 when exports reached US$1.4 billion, largely driven by an expansion of mining activities in conflict-affected regions, particularly in Kachin State, according to ISP – Myanmar, which discovered facts similar to those by Global Witness.

“Satellite imagery confirms a marked rise in illegal, unregulated mining activities, involving both military-backed entities and ethnic armed organisations, exacerbating environmental and social challenges,” ISP – Myanmar noted in its latest report titled, “Unearthing the Cost: Rare Earth Mining in Myanmar’s War-Torn Regions”, released in June this year.

It is widely believed that a significant amount of the revenue has returned to those armed groups or organisations to support their economy and security in their territories.

As analysed by Stimson fellow Amara Thiha in his article: “Rare Earths and Realpolitik: Kachin Control, Chinese Calculus, and the Future of Mediation in Myanmar“, published in June this year, mining resources and controls over them, especially rare earths, have leveraged the power and legitimacy of these non-state actors in political diplomacy.

Citing the case of the Kachin Independent Army (KIA)’s control of the rare earth mining in Chipwe and Pangwa in Kachin State, the author noted that the resource control there has redefined the group’s strategic role: It is no longer solely a territorial armed group. The KIA governs key resource zones, manages export taxation and negotiates directly with a major regional power, he said.

And this is not without precedent, he added. In the wake of its 1994 ceasefire with the military-ruling government, the KIA administered jade mining in Hpakant, using revenues to entrench its autonomy and build administrative capacity, the author noted.

The UWSA itself also has a long history of trade with China by exporting tin from Wa State to the country. This armed group operates a system of informal taxation, providing stable access to resources in exchange for political non-interference, and the KIA’s role is beginning to resemble that of the UWSA, according to the author.

He also analysed their background differences as well as attempts of major powers, including China, the U.S. and even India, to gain access to the mining resources in armed groups’ territories that could influence diplomacy and stability in Myanmar. One thing is clear: these armed groups or organisations have been leveraged with so-called resource-backed diplomacy.

According to him, they have been negotiating with China directly for business in these resources, having a joint platform — the Federal Political Negotiation and Consultative Committee — that acts as a vehicle for China’s informal engagement. It is a coalition of ethnic armed organisations led by the UWSA.

“Whether this model of resource-backed diplomacy can produce stability remains uncertain. What is clear is that rare earths now shape the political landscape of northern Myanmar. Rebel governance, cross-border trade and great power rivalry are converging in a zone once seen as peripheral…

“Control over territory and extraction sites has created leverage, reinforcing the perception among ethnic armed organisations, the National Unity Government, and People’s Defense Forces that China will pragmatically engage with whoever holds power on the ground,” said the author.

Bangkok Tribune has sent a set of queries to China’s representatives through the Chinese embassy in Thailand, but so far there has been no response from the embassy.

Photo: ©Thiti Wannamontha

Local fights

Downstream, the first movement of Thaton residents has gained momentum and expanded to wider areas, including downstream Chiang Rai and as far as Bangkok and the regional and international community.

Despite the widespread public awareness and acknowledgement, the people involved with the issue are still struggling to find proper solutions due to its complexity.

Pianporn Deetes, Executive Director of Rivers and Rights Foundation and a former Southeast Asia campaign director for the International Rivers, has expressed her frustration about the issue. As an advocate who has long campaigned for sustainable development and river conservation in the Mekong Region for more than 20 years, she said unlike hydropower development in the Lower Mekong, it is clear that this toxic contamination issue is an environmental crime that people can see with their eyes.

It is unregulated toxic pollution that can kill people, but so far, there have not been clear solutions or directives to address the issue, especially from her government, she said.

She and her fellow advocates in the new network of civil society groups and academics in the affected areas, the People’s Network to Protect the Kok, Sai, Ruak, and the Mainstream Mekong rivers, have been campaigning about this issue since the first days, along with Thaton residents. They have come up with a radical proposal, calling on the concerned agencies and governments to stop mining upstream, a proposal that people say is literally impossible to implement, although it addresses the root cause of the problem downstream.

The Thai government, however, lacks a strong political will to address the issue and solve the problem, especially by dealing with the root cause. She suspects that there have been conflicts of interest at play in this issue.

“I don’t see a strong intention in the government to solve the problem. I cannot see any tangible solutions from it. People said it’s hard to talk with non-state actors, but I believe it would not be totally impossible if we wanted to solve the problem. The point is whether you have tried it yet. So far, I have not seen the Thai government set its firm position on the issue yet,” said Ms. Pianporn.

Photo: ©Bangkok Tribune

Since the issue broke out, the government, under a directive from then PM Paetongtarn Shinawatra, had appointed Deputy PM Prasert Chantararuangtong to direct state agencies concerned to deal with the situation. New sub-panels had been set up under a national committee chaired by him to help address different aspects of the issue, including mitigation of the toxic impacts.

The most striking project they had proposed was the construction of a series of consecutive dams to intercept the heavy metals that flow downstream, a proposal that the local residents and several civil society groups strongly opposed for fear that it could exacerbate the situation instead.

Aside from that was the routine testing and monitoring of possible contamination in river water and sediments, fish in the rivers, vegetables from riverside fields, tap water, groundwater, and people’s health in communities near the rivers. This key government monitoring mechanism continues through local government agencies, even under the new Anutin Charnvirakul government, which entered office a few weeks ago.

Mr. Prasert was also pressured to discuss the issue with the concerned parties, and his committee set eyes to initiate the talks with the de facto Myanmar government. It was not until late August that his committee managed to discuss with Myanmar’s de facto government in Naypyidaw. It had only one achievement: the creation of a joint monitoring operation for the Kok, Sai, and Ruak rivers.

Courtesy of ©ThaiGov

Mr. Eyler, who has been following the issue, said monitoring can inform a better policy response. Still, it is unlikely to curb the activity of the Chinese mine operators in Myanmar.

These miners, he said, operate in territories totally out of reach of the state and stopping the mining would also require the involvement of Beijing or other political actors in China, who, he said, so far have shown zero motivation to address the issue.

Niwat Roykaew, the chairperson of Chiang Khong Conservation Group and the winner of the 2022 Goldman Environmental Prize, and other scholars in the areas, including Asst. Prof. Dr. Satian Chunta from Chiang Rai Rajabhat University’s natural resources and environmental management division, and a member of the Northern Mekong watershed committee, and Dr. Suebsakul Kitnukorn of the Mae Fah Luang University’s Area-based-Social Innovation Research Center have realised well the complexity of the issue.

They have analysed the mining activities upstream to supply chains and global markets downstream, and realised that this problem is “a disaster”.

The scholars agreed that there was a need to talk with the armed groups involved and China seriously, and there is a need for the Thai government to come up with a concrete set of information and data, as well as a substantial body of knowledge on this issue, so that it can come up with proper policy responses and solutions.

No such thing exists, Dr. Satian, who has been pushing for the establishment of a new data centre to help aggregate information in all aspects and formulate corresponding policies, lamented.

Mr. Niwat, who has been fighting unsustainable hydropower development in the Mekong region, views that the Thai government alone can no longer talk to these parties, given the complexity of the issue.

He said it is time for the issue to be raised at a regional and international level, so it could gain support from the regional and international community, such as the blocs of the Mekong River Commission (MRC), the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation (LMC), ASEAN, or even the UN. More critically, people must be allowed to be a part of the problem-solving processes, he said.

For Phra Maha Nikhom, the success in solving this problem also depends on the people, as they can help push for sound solutions. They can be part of the solutions, and they must be a part of it, given that the problem is also their own, the senior monk who guides the people’s spirits said.

“Some residents have worked hard on this, but they say they feel desperate as their action is amounting to nothing. I myself have never felt hopeless about it.

“At least”, the spiritual monk continues, “you have learned along the way. You have learned about new methods, met more people, and gained new skills and experiences. All of these help you grow stronger and deal with something more challenging, including this problem.

“Every problem in this world can be resolved, but whether it happens sooner or later is another matter. It also depends on your strength and how you grow — socially and intellectually,” said the spiritual monk, expressing his intellectual thoughts in a calm and soft-toned voice.

Photo: ©Thiti Wannamontha

Also read and see photos: PHOTO ESSAY: Living in Fear

This special report is part of the SPECIAL REPORT SERIES: Environmental Challenges under the Great Power’s Influences.

Environmental Challenges under the Great Power’s Influences

In March this year, toxic heavy metal contamination in the Kok, Sai, and Mekong Rivers surfaced for the first time. Residents in Thaton village, on the Thailand-Myanmar border in Mae Ai district of Chiang Mai province, marched to protest mining activities along the border, which they claimed were polluting their rivers.

Since then, more information has emerged, revealing a connection to China’s investments. While gold mining is ongoing, residents suspect that mining for Rare Earth minerals, critical to technologies such as EVs, is also taking place.

This has further complicated the issue. The Thai government is trying to convince all parties to consider local livelihoods and environmental impacts — but to no avail.

The toxic contamination of the country’s lifelines by cross-border mining has once again demonstrated how China and its investments have influenced, and increasingly played a role in, local development and environmental health in the Mekong region.

This newest issue follows several unsettled development projects and struggles involving China, such as the hydropower development on the Mekong River, the intra-regional transportation mega-project of the Belt and Road Initiative, Chinese recycling plants, and more.

All these have caused conflicts with local residents, triggered serious environmental problems in the country and region, challenged existing laws and regulations, undermined the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and heightened geopolitical tensions.

To keep up with the trend and inform the public so they can engage in discussions and solutions on these critical issues together, Bangkok Tribune, with the support of Konrad Adenauer Stiftung Thailand, has accordingly launched the series: Environmental Challenges under the Great Power’s Influences.