The latest marine forensics performed by a team at the Department of Marine and Coastal Resources has revealed a rising challenge against one of the country’s reserved marine animals, Bryde’s Whale, in the busy shipping lanes in the Inner Gulf of Thailand, part of its largest habitat in Asia

“In conclusion, the death was a result of being hit straight by a hard object with high centrifugal force, resulting in severe bleeding that caused a body shock following severe blood loss and great pain.”

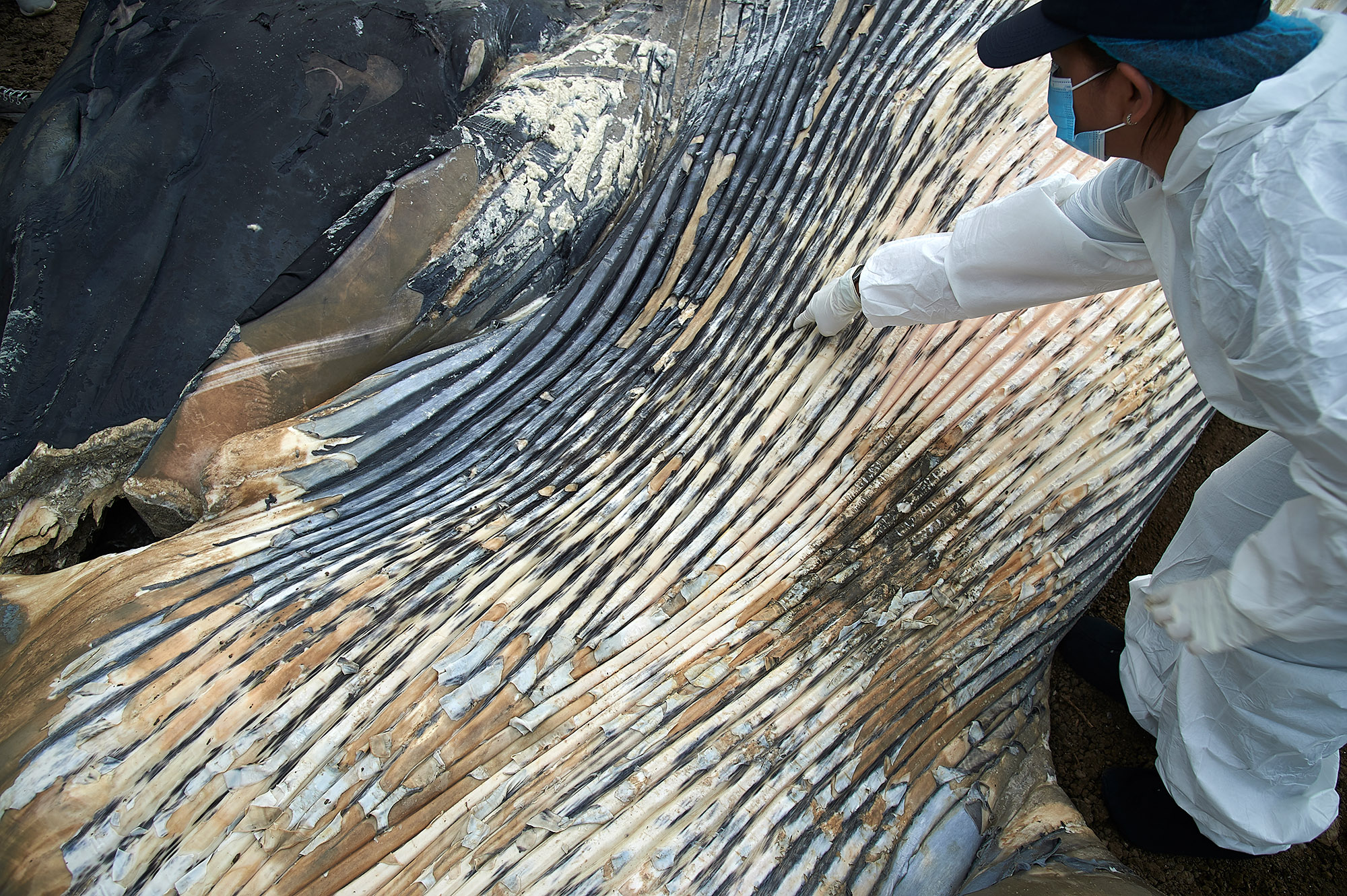

It’s around her head that the DMCR’s marine forensics team referred to in their autopsy result report sent to the department this weekend.

According to the report, there were some critical wounds and deep cuts on her upper jaw, lower jaw, right chin, and occipital bone. As a result, the left side of her skull was broken, and the bone around the tip of the upper jaw and both sides of the lower jaw of hers were broken, the condition called by the forensic team a complete transverse fracture.

While her body was still in good condition, there was a cut on the tip of her left shoulder blade, suggesting that the area was also hit by a hard object with high centrifugal force. The tissue surrounding the wound was bruised with wide blood congestion, and on her back, there was a 160-cm-long bruise.

Severe blood congestion was also detected in the left of her lung. Other internal organs, the liver, spleen, kidneys, pancreas, and her reproductive system, have decayed. What also beyond recognition are the marks on her dorsal fins and around the edge of her mouth.

“At this point, I can’t tell who she was,” said Dr. Rachawadee Chantra D.V.M, Marine Veterinarian, Professional Level, of the DMCR’s Marine and Coastal Resources Research Center (Upper Gulf of Thailand), who checked the dead body round and round despite risks of possible diseases or toxins and bad odour.

Dr. Racharawadee led the team, which was comprised of some ten veterinarians and assistants from other departments including the Fisheries Department, to examine the dead Bryde’s whale aged 3 years old found floating offshore in Tambon Bang Pu Main in Samut Prakan province neighbouring Bangkok over the weekend until the mystery of her death was resolved.

The unidentified young whale with critical marks damaged beyond recognition is not the first found dead in the Inner Gulf of Thailand. Her death has just repeated the previous incident and reminded concerned authorities of the challenge that keeps rising in the busy shipping lanes of the Gulf, which is the largest home of the species in Asia.

Bryde’s whales are found in warm, temperate oceans, including the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific. According to the NOAA’s Fisheries, they are considered one of the “great whales”, or rorquals, which is a group that also includes blue whales and humpback whales. Some populations of Bryde’s whales make short migratory movements with the seasons, while others do not migrate, making them unique among other migrating baleen whales, the organisation notes.

Here in the Gulf of Thailand, Bryde’s whales make seasonal migration between the Inner Gulf and the South, making them generally residents of the Gulf of Thailand, according to the research center’s director, Chalatip Junchompoo. Ms. Chalatip said there is no scientific evidence confirming the migration of Bryde’s whales from the Gulf of Thailand to the South China Sea, and there is a concern about genetic variation among the population in the future. For this reason, the department prioritizes genetic studies to understand the genetic relationships of Bryde’s whale populations in the region.

According to the latest statistics produced by her centre, this 16th reserved animal and one of the first three marine animals registered under the Wildlife Conservation and Preservation Act B.E. 2562 has around 156 animals inhabiting the Gulf, given their identical marks and photo IDs the centre has collected.

Based on their death rate, 1-2 animals a year, compared with the birth rate of 10% a year, their population trend is not yet worrisome, according to Ms. Chalatip, given that the natural death rate of the species worldwide is at 5%. However, when considering other factors including human activities that have caused a rise in marine animals’ stranding in the area in recent years, the centre has paid serious attention to every death that occurs in its responsible areas and reported to the department so as for it to come up with appropriate measures to address all possible challenges.

So far, the department has pointed out that the young whale died as a result of a boat propeller. Ms. Chalatip noted that the whales’ habitat in the Inner Gulf is the area which overlaps with a regular route of large cargo ships and vessels. According to the Marine Knowledge Hub website, a knowledge-based platform developed by the department in partnership with other departments and academic institutions, the Inner Gulf alone has up to 86 ports, and the one in Bangkok’s Khlong Toey area is the country’s second largest.

The noted marine scientist, Dr. Thon Thamrongnawasawat, posted on his Facebook Page upon learning about the bad news that it’s truly tragic because if she could live up to 10 years and start to give births, she would give offsprings at least 20 or so throughout her life span of 50 years.

“But now she has no chance of becoming a mother, no chance to be a grandmother watching her little grandchild learning to feed by leaping out of the water with their wide open mouth and snap fish. This is truly tragic,” said Dr. Thon.

Dr. Thon noted that in recent years, vessel strikes have increasingly become a cause of the death of large whales worldwide, and scientists have been trying to address the issue by coming up with solutions such as the installation of devices to detect or locate the animals so as for them to reduce their speed to avoid crashes or issue out a warning or advanced notices to other vessels nearby.

However, these measures could not be practical in the Gulf as a large number of vessels busily travel in and out of the area where whales freely feed and breed. The scientists here ever proposed declaring the area as a protection zone for whales and dolphins, but to no avail.

“The problem is not easy to resolve. As animals’ homes become busy shipping lanes, it’s “nature” that feels pain,” said Dr. Thon.

Ms. Chalatip said the department has been attempting to protect the endangered animals in the area by conducting regular marine patrolling over their habitats. The DMCR’s Director-General, Dr. Pinsak Surasawadi, has provided policy direction and support for integrating Smart Patrol technology into the efforts. But the sea is too vast to take care of, she admitted.

That is the reason why the animals themselves and their safety have become a focus. The department has tried to keep concerned authorities informed, the Marine Department included, about the animals’ distribution so as for them to become aware of their existence and issue appropriate measures in their responsible areas to help save them. Networking with concerned agencies as well as coastal communities has also been forged to support the work, she said.

As the young whale was apparently hit by a boat strike, it’s time for concerned authorities to come and discuss the possible measures to address the issue, she said, adding it’s a responsibility to society to put delicate sights and observations in place when travelling at sea.

The department now needs scientific proof to initiate the talks, and that’s the reason why marine forensics is crucial for the task as it helps resolve the death mysteries of the endangered animals there as well as the challenges involved, she said.

“We could, bit by bit, tissue by tissue, resolve mysteries over human-induced incidents, diseases or even toxins that cause them injured or dead and that’s crucial as that could also mean our survival in the future too,” said Dr. Racharawadee. “Marine forensics and autopsy results are a very good biological identification tool that helps guide us to sound measures and policies in managing our marine resources. They give us the answers to unresolved mysteries and challenges we need to address.”

So far, there are no more than ten marine veterinarians like Dr. Racharawadee who perform marine forensics in the country. It’s relatively new in the field of veterinary science, following the increasing popularity of wildlife forensics some years back. The field needs concrete science in marine biology alongside, and no direct course of this specific body of knowledge is provided at a university to students who are interested in it. Dr. Racharawadee herself also had to take some related courses overseas before applying for a job at the department over 13 years ago.

Asked why she still works in this field despite all the hard work she has to shoulder, she said; “I love whales and dolphins for a long, long time, and it’s love for them that keeps me at the job.”

Photo: Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Photo: Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Photo: Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Photo: Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Photo: Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Photo: Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Photo: Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Photo: Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Photo: Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Photo: Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Photo: Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Photo: Sayan Chuenudomsavad

The team takes almost half a day to skin the whole body.

Photo: Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Photo: Sayan Chuenudomsavad

A daunting task amid various risks, including possible diseases or toxins from the dead animal.

Photo: Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Photo: Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Photo: Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Photo: Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Photo: Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Photo: Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Photo: Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Indie • in-depth online news agency

to “bridge the gap” and “connect the dots” with critical and constructive minds on development and environmental policies in Thailand and the Mekong region; to deliver meaningful messages and create the big picture critical to public understanding and decision-making, thus truly being the public’s critical voice