Over 50% of corals in at least three of those parks have already experienced bleaching whereas the situation worldwide has registered the 4th global event on record

The Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation (DNP) has been monitoring the phenomenon, which is occurring in both the Gulf of Thailand and the Andaman, affecting its protected marine parks. As reported to the DNP’s chief, Athapol Charoenshunsa, corals in 12 national marine parks under its supervision have been experiencing coral bleaching in a depth of seawater less than two metres since early last month.

They include six national parks on the side of the Gulf of Thailand; Mu Koh Chang, Khao Laem Ya-Mu Koh Samed, Sam Roi Yod, Had Vanakorn, Mu Koh Chumpon, and Had Khanom-Mu Koh Thale Tai. The other six parks on the side of the Andaman include Mu Koh Surin, Sirinat, Ao Phang-nga, Than Bokkoranee, Had Nopparat Tara-Mu Koh Phi Phi, and Lan Ta.

Corals in three of these marine parks have faced bleaching up to 50-80%, prompting the department to close some of them to lessen the impact. Sirinat National Park in Phuket province was included. The department suspected that the warmer seas have contributed to this phenomenon.

The Marine and Coastal Resouces Department has also been instructed by the Environment Ministry to help lessen the bleaching impact, and if necessary, must move coral nurseries to deeper, cooler water or deploy sunshades to protect the corals.

Coral bleaching, as explained by NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration), is the phenomenon when corals are stressed by changes in conditions such as temperature, light, or nutrients. They tend to expel the symbiotic algae (zooxanthellae) living in their tissues, causing them to turn completely white. When a coral bleaches, the organisation says it is not dead. Corals can survive a bleaching event, but they are under more stress and are subject to mortality.

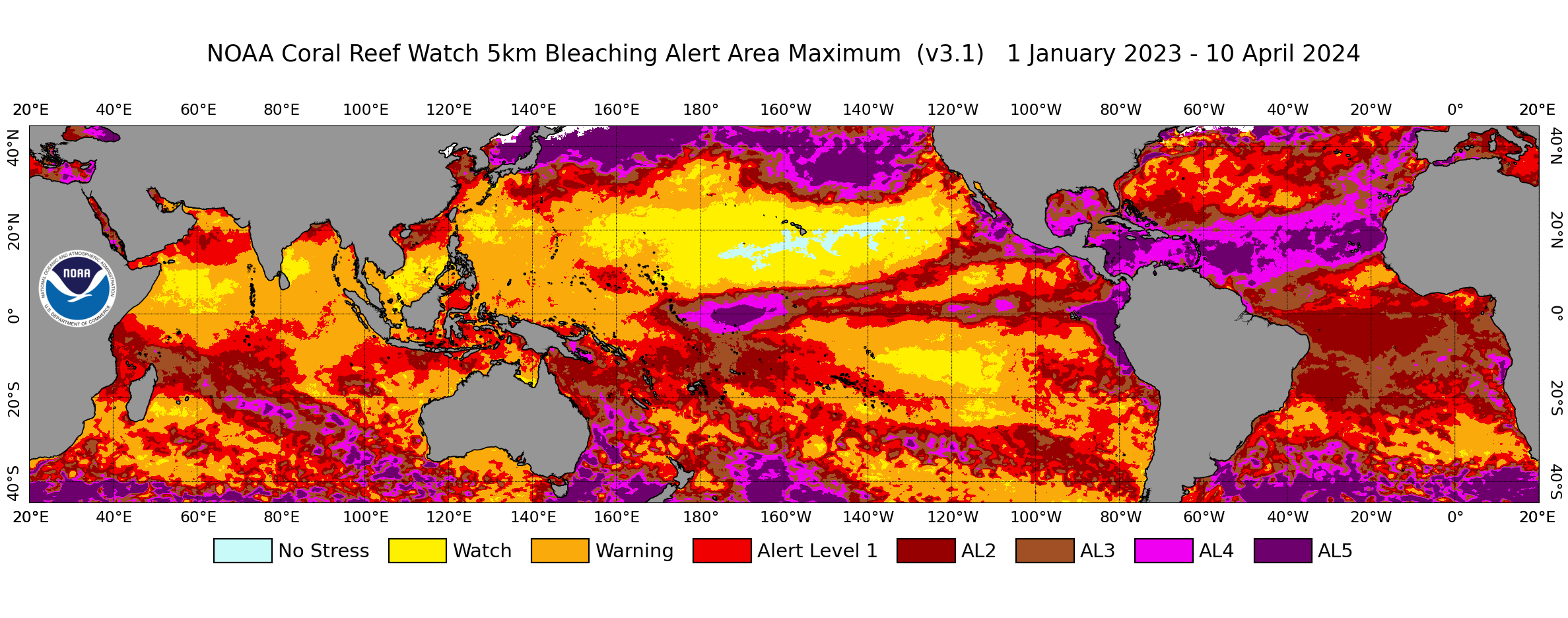

l The map showing 12 parks under watch for coral bleaching by the DNP at the moment. If the stress-caused bleaching is not severe, corals have been known to recover. If the algae loss is prolonged and the stress continues, coral eventually dies, NOAA said. Credits: DNP/ NOAA

Dr. Pinsak Suraswadi, the DMCR’s chief, said coral bleaching is a global phenomenon which affects corals’ growth. In order for them to recover from the bleaching impact, it may take up to 5 to 10 years, he said. In Thailand, the bleaching occurred twice within the past ten years, prompting the corals to become incapable of regenerating in time. He has acknowledged the global phenomenon, which is taking place elsewhere as well. The DMCR’s chief said the department is monitoring the warming seas and is on alert to deploy any further assistance as needed.

The rising sea temperature is also being suspected of causing the death of seagrass in Trang province, where a major pod of dugongs inhabit. It also likely affects the breeding of sea turtles as male turtles become fewer, prompting the eggs to fail to hatch.

“The ‘Global Boiling” phenomenon needs to be closely monitored as it’s not a joke. What’s happening is real and would leave no further marine resources for us to pass on to the next generations, “said Dr. Pinsak.

In an attempt to fight climate change and global boiling, the department is conducting studies to look at the causes of these phenomena so that it can deploy the most effective solutions against climate impact.

The 4th bleaching on record

In mid-April, NOAA released its latest observation on the bleaching worldwide, concluding that the phenomenon is the fourth global event on record and the second in the last 10 years. “The world is currently experiencing a global coral bleaching event,” said NOAA scientists.

Bleaching-level heat stress has been and continues to be extensive across the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Ocean basins, according to NOAA’s Coral Reef Watch (CRW), which bases its heat-stress monitoring on sea surface temperature data spanning 1985 to the present.

From February 2023 to April 2024, significant coral bleaching has been documented in both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres of each major ocean basin, said NOAA CRW coordinator, Dr. Derek Manzello.

Since early 2023, mass bleaching of coral reefs has been confirmed throughout the tropics including Florida in the U.S., the Caribbean, Brazil; the eastern Tropical Pacific including Mexico, El Salvador, Costa Rica, Panama and Colombia, Australia’s Great Barrier Reef; large areas of the South Pacific including Fiji, Vanuatu, Tuvalu, Kiribati, the Samoas and French Polynesia; the Red Sea including the Gulf of Aqaba; the Persian Gulf; and the Gulf of Aden, according to NOAA.

The confirmation was made on widespread bleaching across other parts of the Indian Ocean basin as well, including in Tanzania, Kenya, Mauritius, the Seychelles, Tromelin, Mayotte and off the western coast of Indonesia, NOAA noted.

“As the world’s oceans continue to warm, coral bleaching is becoming more frequent and severe,” Dr. Manzello said. “When these events are sufficiently severe or prolonged, they can cause coral mortality, which hurts the people who depend on the coral reefs for their livelihoods.”

As explained by NOAA, coral bleaching, especially on a widespread scale, impacts economies, livelihoods, food security and more, but it does not necessarily mean corals will die. If the stress driving the bleaching diminishes, corals can recover and reefs can continue to provide the ecosystem services people rely on. But this process usually takes time.

Director of NOAA’s Coral Reef Conservation Program (CRCP) Jennifer Koss pointed out similarly that climate model predictions for coral reefs have been suggesting for years that bleaching impacts would increase in frequency and magnitude as the ocean warms.

The 2023 heatwave in Florida was unprecedented, for instance. It started earlier, lasted longer and was more severe than any previous event in that region. During the bleaching event, NOAA learned a great deal while engaging in interventions to mitigate harm to corals, including moving coral nurseries to deeper, cooler waters and deploying sunshades to protect corals in other areas.

The organisation said this is a global event that requires global action. The international community is sharing and already applying resilience-based management actions and lessons learned from the 2023 marine heatwaves in Florida and the Caribbean through international platforms, including the International Coral Reef Initiative (ICRI), said NOAA.

Indie • in-depth online news agency

to “bridge the gap” and “connect the dots” with critical and constructive minds on development and environmental policies in Thailand and the Mekong region; to deliver meaningful messages and create the big picture critical to public understanding and decision-making, thus truly being the public’s critical voice