A new UN flagship report calls for a fundamental reset of the global water agenda as irreversible damage pushes many basins beyond recovery

A UN report released this week has declared “the dawn of an era of global water bankruptcy”, inviting world leaders to facilitate honest, science-based adaptation to a new reality amid chronic groundwater depletion, water overallocation, land and soil degradation, deforestation, and pollution, all compounded by global heating.

The UN’s Think Tank on Water’s report, “Global Water Bankruptcy: Living Beyond Our Hydrological Means in the Post-Crisis Era,” argues that the familiar terms “water stressed” and “water crisis” fail to reflect today’s reality in many places: a post-crisis condition marked by “irreversible losses” of natural water capital and an inability to bounce back to historic baselines.

The report is issued prior to a high-level meeting in Dakar, Senegal (Jan 26-27) to prepare the 2026 UN Water Conference, to be co-hosted by the United Arab Emirates and Senegal, Dec 2-4, in the UAE.

“This report tells an uncomfortable truth: many regions are living beyond their hydrological means, and many critical water systems are already bankrupt,” said lead author Kaveh Madani, Director of the UN University’s Institute for Water, Environment and Health (UNU-INWEH), known as “The UN’s Think Tank on Water”.

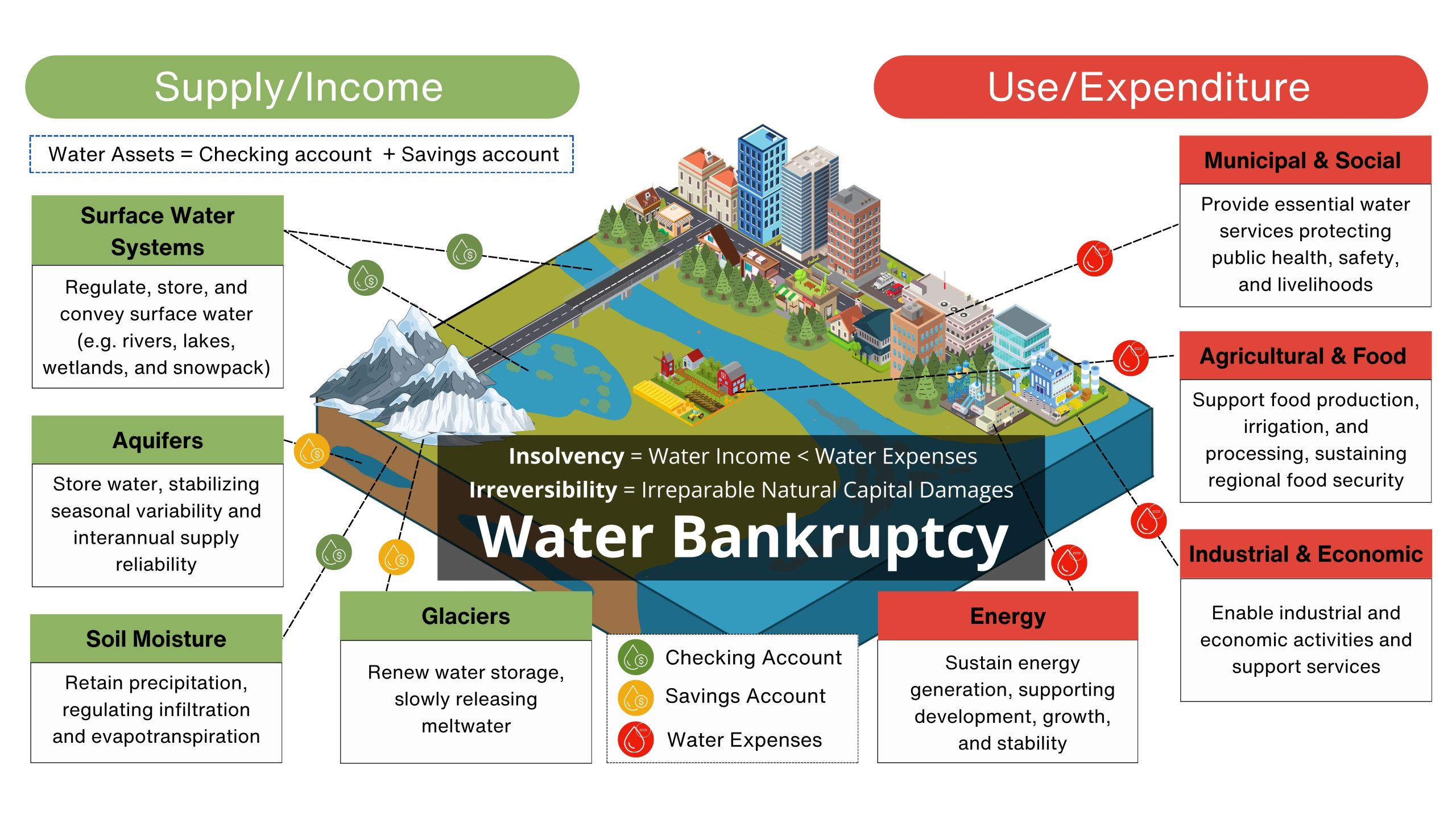

Expressed in financial terms, the report says many societies have not only overspent their annual renewable water “income” from rivers, soils, and snowpack, but they have also depleted long-term “savings” in aquifers, glaciers, wetlands, and other natural reservoirs.

This has resulted in a growing list of compacted aquifers, subsided land in deltas and coastal cities, vanished lakes and wetlands, and irreversibly lost biodiversity.

The report is based on a peer-reviewed paper to be published in the Journal of Water Resources Management, which formally defines “water bankruptcy” as persistent over-withdrawal from surface and groundwater relative to renewable inflows and safe levels of depletion, and the resulting irreversible or prohibitively costly loss of water-related natural capital.

By contrast, “water stress” reflects high pressure that remains reversible, while “water crisis” describes acute shocks that can be overcome.

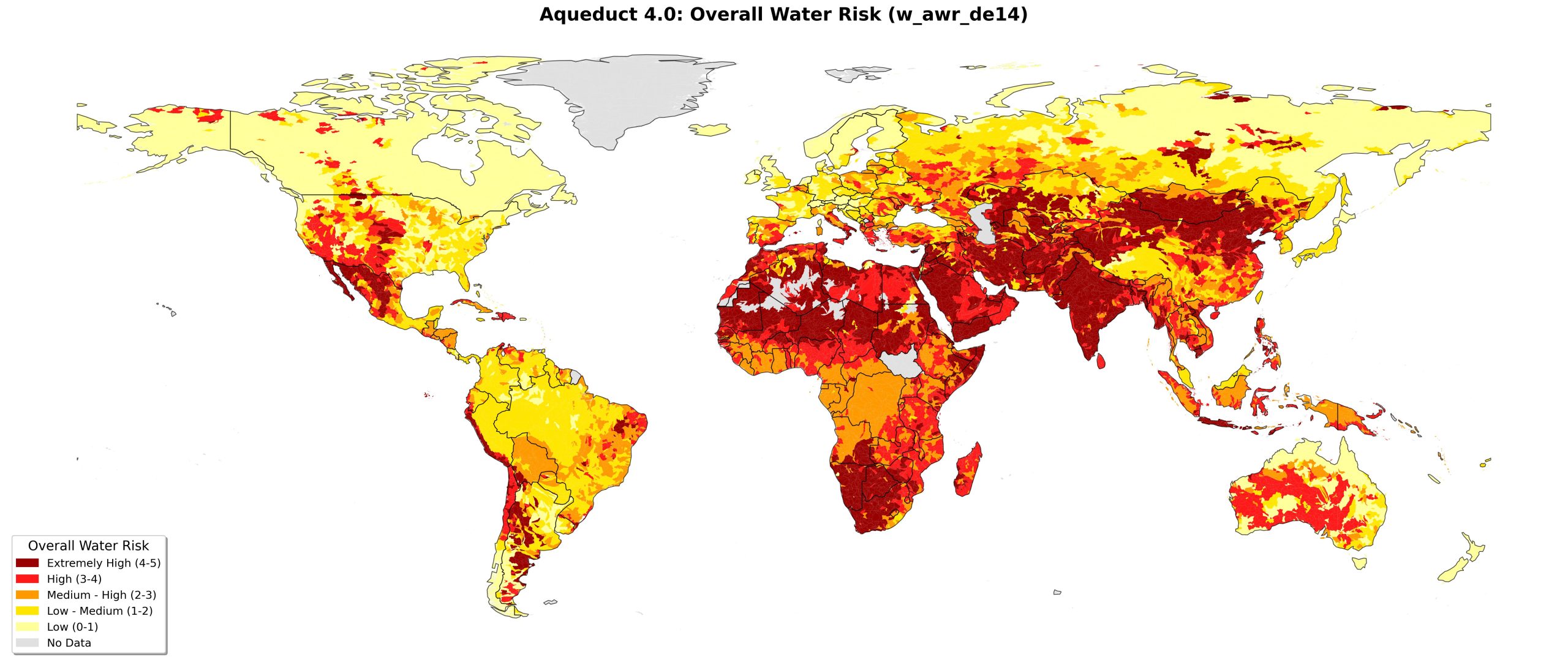

While not every basin and country is water-bankrupt, Mr. Madani said enough critical systems around the world have crossed these thresholds. These systems are interconnected through trade, migration, climate feedbacks, and geopolitical dependencies, so the global risk landscape is now fundamentally altered, he added.

A new diagnosis for a new era

Mr. Madani said a region can be flooded one year and still be water bankrupt if long-term withdrawals exceed replenishment. In that sense, water bankruptcy is not about how wet or dry a place looks, but about balance, accounting, and sustainability.

As with global climate change or pandemics, a declaration of global water bankruptcy does not imply uniform impact everywhere, but that enough systems across regions and income levels have become insolvent and crossed irreversible thresholds to constitute a planetary-scale condition.

“Water bankruptcy is also global because its consequences travel,” Mr. Madani explained. “Agriculture accounts for the vast majority of freshwater use, and food systems are tightly interconnected through trade and prices. When water scarcity undermines farming in one region, the effects ripple through global markets, political stability, and food security elsewhere. This makes water bankruptcy not a series of isolated local crises, but a shared global risk that demands a new type of response: Bankruptcy management, not crisis management.”

A world in the red

Drawing on global datasets and recent scientific evidence, the report presents a stark statistical overview of trends, the overwhelming majority caused by humans:

- 50%: Large lakes worldwide that have lost water since the early 1990s (with 25% of humanity directly dependent on those lakes)

- 50%: Global domestic water now derived from groundwater

- 40%+: Irrigation water drawn from aquifers being steadily drained

- 70%: Major aquifers showing long-term decline

- 410 million hectares: Area of natural wetlands – almost equal in size to the entire European Union – erased in the past five decades

- 30%+: Global glacier mass lost since 1970, with entire low- and mid-latitude mountain ranges expected to lose functional glaciers altogether within decades

- Dozens: Major rivers that now fail to reach the sea for parts of the year

- 50+ years: How long many river basins and aquifers have been overdrawing their accounts

- 100 million hectares: Cropland damaged by salinisation alone

The report also presents the human consequences:

- 75%: Humanity in countries classified as water-insecure or critically water-insecure

- 2 billion: People living on sinking ground

- 25 cm: Annual drop being experienced by some cities

- 4 billion: People facing severe water scarcity for at least one month every year

- 170 million hectares: Irrigated cropland under high or very high water stress – equivalent to the areas of France, Spain, Germany, and Italy combined

- US$5.1 trillion: Annual value of lost wetland ecosystem services

- 3 billion: People living in areas where total water storage is declining or unstable, with 50%+ of global food produced in those same stressed regions

- 1.8 billion: People living under drought conditions in 2022–2023

- US$307 billion: Current annual global cost of drought

- 2.2 billion: People who lack safely managed drinking water, while 3.5 billion lack safely managed sanitation

In the Middle East and North Africa region, high water stress, climate vulnerability, low agricultural productivity, energy-intensive desalination, and sand and dust storms intersect with complex political economies, the report notes on the world’s hotspots.

In parts of South Asia, groundwater-dependent agriculture and urbanisation have produced chronic declines in water tables and local subsidence. And in the American Southwest, the Colorado River and its reservoirs have become symbols of over-promised water.

A call to reset the global water agenda

The report warns that the current global water agenda – largely focused on drinking water, sanitation, and incremental efficiency improvements – is no longer fit for purpose in many places and calls for a new global water agenda that:

- Formally recognises the state of water bankruptcy.

- Recognises water as both a constraint and an opportunity for meeting climate, biodiversity, and land commitments.

- Elevates water issues in climate, biodiversity, and desertification negotiations, development finance, and peacebuilding processes.

- Embeds water-bankruptcy monitoring in global frameworks, using Earth observation, AI, and integrated modelling.

- Uses water as a catalyst to accelerate cooperation between the UN Member States.

In practical terms, managing water bankruptcy requires governments to focus on the following priorities:

- Prevent further irreversible damage such as wetland loss, destructive groundwater depletion, and uncontrolled pollution.

- Rebalance rights, claims, and expectations to match the degraded carrying capacity.

- Support just transitions for communities whose livelihoods must change.

- Transform water-intensive sectors, including agriculture and industry, through crop shifts, irrigation reforms, and more efficient urban systems.

- Build institutions for continuous adaptation, with monitoring systems linked to threshold-based management.

“Water bankruptcy is not merely a hydrological problem, but a justice issue with deep social and political implications requiring attention at the highest levels of government and multilateral cooperation.

“The burdens fall disproportionately on smallholder farmers, Indigenous Peoples, low-income urban residents, women and youth while the benefits of overuse often accrued to more powerful actors,” underlines the report.

UN Under-Secretary-General Tshilidzi Marwala, Rector of UNU, said: “Water bankruptcy is becoming a driver of fragility, displacement, and conflict. Managing it fairly – ensuring that vulnerable communities are protected and that unavoidable losses are shared equitably – is now central to maintaining peace, stability, and social cohesion.”

Mr. Madani added: “Bankruptcy management requires honesty, courage, and political will. We cannot rebuild vanished glaciers or reinflate acutely compacted aquifers. But we can prevent further loss of our remaining natural capital, and redesign institutions to live within new hydrological limits.”

Upcoming milestones, the 2026 and 2028 UN Water Conferences, the end of the Water Action Decade in 2028, and the 2030 SDG deadline, for example, provide critical opportunities to implement this shift, Mr. Madani said.

“Despite its warnings, the report is not a statement of hopelessness. It is a call for honesty, realism, and transformation,” Madani added. “Declaring bankruptcy is not about giving up; it is about starting fresh. By acknowledging the reality of water bankruptcy, we can finally make the hard choices that will protect people, economies, and ecosystems. The longer we delay, the deeper the deficit grows.”

Source: UNU-INWEH’s report, “Global Water Bankruptcy: Living Beyond Our Hydrological Means in the Post-Crisis Era”

Indie • in-depth online news agency

to “bridge the gap” and “connect the dots” with critical and constructive minds on development and environmental policies in Thailand and the Mekong region; to deliver meaningful messages and create the big picture critical to public understanding and decision-making, thus truly being the public’s critical voice