On January 16, a critical energy policy forum organised by JustPow presented a slate of unified policy demands from civil society, businesses, and academia to major political parties. One of the most controversial, yet essential, proposed policy positions was the urgent call to halt all future Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) for new hydropower projects on the Mekong River.

The political response was deeply divided: Bhumjaithai, People’s, and United Thai Nation Parties agreed with the proposed halt, while the Democrat, Thai Sang Thai, and Thai Kao Mai Parties voiced disagreement. Pheu Thai remained unsure, and the remaining parties declined to weigh in.

This division revealed a major concern: many of Thailand’s political parties and leaders might still have an outdated view of large hydropower as necessary and beneficial to Thailand’s energy future.

It is crucial that this information gap is urgently addressed, given that each political party, the future Energy Minister and the country’s energy planners will be finalising Thailand’s next Power Development Plan (PDP) in the months to come. Imports from tropical hydropower are neither cheap, clean, nor reliable.

Not Low-Carbon: Tropical hydro has a hidden carbon cost

The most dangerous assumption underpinning the hydropower dream is that it is a ‘clean’ or ‘low-carbon’ energy source.

The widely cited low Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emission value of 24 gCO2eq/kWh for hydropower is highly misleading, especially for dams in tropical regions like Southeast Asia. This Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)-derived figure is based on a limited selection of studies focused primarily on temperate environments (U.S., Switzerland, Norway), where reservoirs have less organic content and much cooler conditions than the tropics.

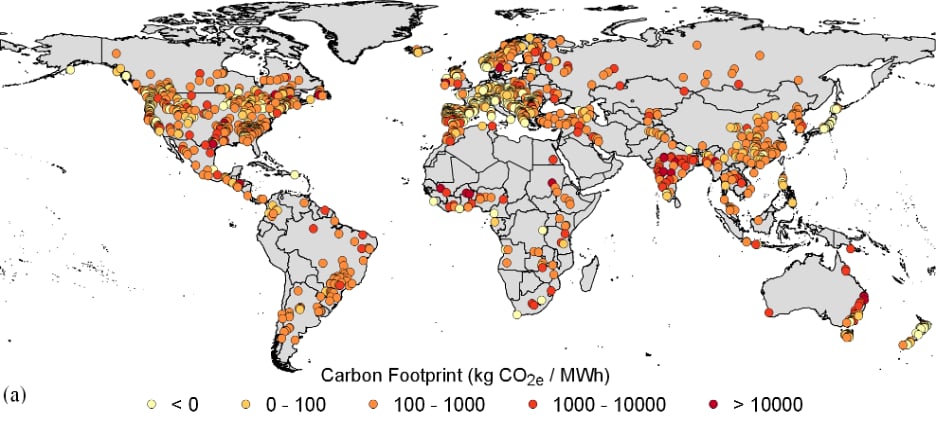

Academic critiques point out that the underlying methodology also significantly underestimates methane emissions, which are 28 times more potent than CO2, and uses outdated metrics. More representative analyses estimate significantly higher emissions (global average of 273 gCO2eq/kWh), with the highest values coming from tropical projects.

Carbon footprints of hydropower plants across the world. Source: Scherer and Pfister (2016) “Hydropower’s Biogenic Carbon Footprint”)

A 2018 study by Timo A. Räsänen, et al., which quantified GHG emissions from Lower Mekong Basin hydropower projects, found these projects have significant methane emissions from reservoirs. The Pak Mun Dam, a “run-of-river” dam similar to proposed Mekong mainstream dams, is estimated to emit a staggering 462 gCO2eq/kWh. Given their similarities, the new hydropower imports from Lao PDR are likely to have a similarly high emission intensity per unit of energy.

Given this study primarily focused on reservoir emissions, the total life-time emissions would be significantly higher, once methane emissions from hydropower operations and decommissioning were factored in. Gas-fired power plants have a carbon intensity of 400-500 gCO2eq/kWh. Tropical hydropower is thus, in reality, no cleaner than electricity from fossil gas.

By importing hydropower, Thailand is effectively outsourcing a significant part of its carbon footprint. We gain the ‘clean’ energy credit on paper while riverine communities in Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam bear the burden of substantial, uncounted GHG emissions. Thailand must not be complicit in this form of environmental greenwashing.

Not Reliable: Hydro imports are “risky” and vulnerable to climate change

Hydropower is lauded for its reliability and dispatchability, but high energy dependence on Laos compromises Thailand’s energy security, a risk amplified by climate change.

Two recent incidents highlight this vulnerability: a 2019 lightning strike on a 500 kV transmission line in Laos caused widespread outages that covered 30 provinces in Thailand, and the sudden trip of the 1200 MW Xayaburi dam led to a 240 MW outage in Thailand in 2025. Compounding this, the Lao national high voltage grid is now 90% controlled by China Southern Power Grid, introducing geopolitical risk for Thai hydropower imports relying on that system for power wheeling.

A Chulalongkorn University study on Thailand’s required reserve margin commissioned by Thailand’s Energy Policy and Planning Office (EPPO) views foreign hydropower as “risky,” suggesting “to maintain the standard level of reliability, the reserve capacity must be increased, or the volume of hydropower imports must be reduced.”

Furthermore, climate change is undermining hydropower’s promised reliability. Before climate change, hydropower production was the lowest when demand was the highest in hot March and April. Laos, the “Battery of Southeast Asia,” now faces severe shortages during peak-demand dry seasons.

A mere 0.5C increase in annual mean maximum temperature is projected to result in a massive drop in Laos’s hydropower capacity factor, from 75% to under 45%, due to increased evaporation and lower water availability. Global models also project increased drought probability for Southeast Asia, with changes potentially leading to a “near total loss of hydropower production” by 2060. Such droughts have already forced Laos to re-import expensive electricity from Thailand; in 2023, these imports reached $240 million.

Not Cheap: Better, cheaper alternatives exist

Since late 2022, Thailand has signed PPAs for three Mekong mainstream dams, the first of which won’t come online till 2030: Luang Prabang (November 2022), Pak Lay (March 2023) and Pak Beng (September 2023) dams, despite the rapidly changing economics of electricity generation.

The price (2.83 baht/kWh) that consumers pay to procure electricity from solar PV bundled with 4 hours of battery energy storage (BESS) is already cheaper than new gas-fired generation and is also cheaper than electricity from Luang Prabang (2.84 baht/kWh).

Meanwhile, the cost of batteries continues to fall precipitously: 40% in 2024 alone. The plunging cost of BESS is making it economically competitive to store solar energy locally, rendering the need for expensive, long-distance transmission from Laos increasingly obsolete.

Instead of costly cross-border power projects and transmission lines, Thailand could prioritize localized solar PV with batteries for firm, dispatchable power and implement demand response programs to reduce peak electricity usage and reliance on expensive imports.

Not Low-Impact: The social and economic cost of outsourcing

Thailand’s demand for imported power has fueled an export-oriented energy strategy in Laos that has become a “debt trap” rather than a ticket out of poverty. This has not only destabilized Laos financially but has also caused severe ecological damage to the Mekong River—including fishery collapse, lost sediment, and biodiversity destruction, which impacts communities along the Mekong in Thailand and beyond.

The reality is that this reliance on imported hydropower is a false climate and energy solution. Thailand must urgently pivot away from new hydro imports and instead invest strategically in clean and cost-effective domestic alternatives like grid flexibility, solar, energy storage, and demand response.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official stance of Bangkok Tribune.

Chuenchom is an inndependent energy researcher.

Pairin is Campaign Manager, Rivers and Rights Foundation.