Rapid development in the Mekong Basin has increasingly caused adverse impacts not only to the mainstream Mekong River but also to its tributaries that have long supported the mainstream, including the so-called last free-flowing Songkhram River of the Northeast, the recent Mekong forum learned

The mainstream Mekong River has once again experienced an unusual change in the water levels as the dams in China released an increasing volume of water discharge downstream over the last week of April. Such an incident becomes countless, having repeatedly raised serious questions about the dam impacts downstream over and over.

Despite increasing public scrutiny in recent years, impacts of the Mekong dams as well as other unsound development projects in the Mekong basin still extensively remain unchecked, especially those affecting the Mekong tributaries_like the Songkhram River Basin in Thailand’s Northeast.

“This is a major challenge that all stakeholders_civil society, educational institutions, the media, as well as the governments_should come and discuss, especially about the aspects concerning the rising threat and the values of these overlooked ecosystems. What is the current situation? How critical is it? What would happen if we have not paid attention to it?” remarked Assoc. Prof. Dr. Kanokwan Manorom, Director of the Mekong Sub-Region Social Research Center, Ubon Ratchathani University’s Faculty of Liberal Arts during the recent special forum, The Songkhram River Basin, the Mekong’s Womb.

It was organised by Bangkok Tribune and its partners, in support of Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. Foundation Office Thailand (KAS Thailand). The forum was part of the opening ceremony of the photo essay exhibition and a book launch recently held at Bangkokthe Art and Culture Centre. The events will be held again at Ubon Ratchathani University next month.

Megaprojects of the Mekong

Originating on the Tibetan plateau in the Qinghai province of China, the Mekong River runs nearly 5,000 kilometres through a wide range of landscapes in six countries and into the South China Sea at the Mekong Delta in Vietnam. (The Mekong River Commission officially notes the length of the river at 4,909 km.)

As researched and noted by the new book, ลุ่มน้ำสงคราม (the Songkhram River Basin) l The Mekong’s Womb, published by Bangkok Tribune, the Mekong River or “Mae Nam Khong” as locally called by Thais and Laotians, is deeply connected with the people, supporting their livelihood and culture to the point that it is classified as another world’s civilization_the Mekong Civilisation.

Throughout the region’s history, the book notes, several ancient kingdoms were built and influenced by the river and its natural cycle, like the famous Funan Kingdom in Vietnam, Chenla as well as Phra Nakhon Kingdoms in Cambodia and Lan Xang of Laos.

While the river has geologically evolved over a million years, it’s within these 40 years that it has seen extensive development that has paved the way for its degradation and deterioration.

The idea to develop the Mekong was first toyed with during the Vietnam War era, the book notes. There was cooperation to establish a working group called the Mekong Committee in 1957, comprising Cambodia, Lao PDR, Thailand and South Vietnam at that time with the support of the United Nations and the United States.

But after the Vietnam War ended in the mid-1970s, political paradigms in the region were clearly divided, posing obstacles to the committee’s work, which was dubbed as a political tool to bring stability to the region through development work.

It was not until 1997 that the regional mechanism was attempted again, this time being renewed as the Mekong River Commission (MRC), under which the four-member countries still keep pushing forward the former committee’s ideas.

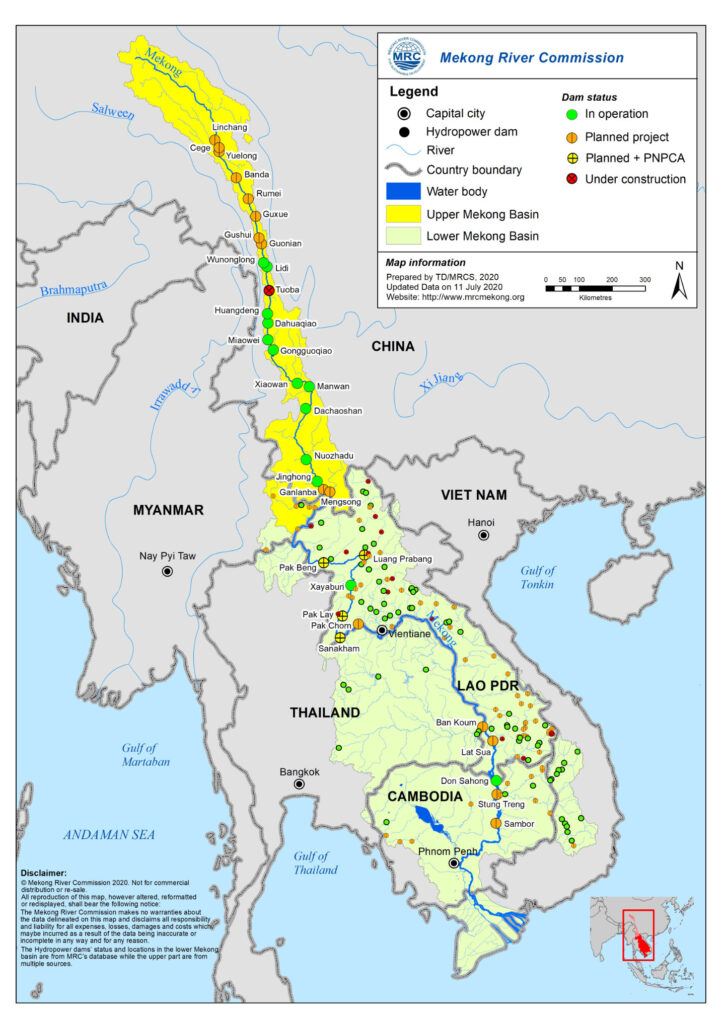

Aside from the MRC member countries, China and Myanmar also have a role in the river development in the region. China, in particular, has come up with a grand project to build a cascade of dams on the mainstream Mekong without recognising the river in the same way as the four countries. It calls the upper part of the river located in its territory “Lancang”, distancing itself from the Lower Mekong countries.

During the 1990s, China extensively dammed the Mekong with a cascade of dams. So far, up to 11 hydropower dams have been built in the Upper Mekong Basin, two of which are large storage dams, the MRC notes. Another 11 dams, each with a production capacity of over 100 megawatts, are being planned or constructed upstream and the total production capacity is estimated at 31,605 MW, increasing from 21,310 MW.

Hydropower is also starting to be developed in a tributary of the Upper Mekong Basin-Myanmar, with the first dam commissioned in 2017 while construction of further dams by both Chinese and Myanmar developers is expected, the MRC further notes, remarking that the overall economic value of hydropower in the upper part of the river is estimated at US$ 4 billion per year.

On the Lower Mekong, meanwhile, 11 other projects have been planned_seven in Laos, two in Cambodia, and two across the Lao-Thai border. Of these, Xayaburi and Don Sahong dams in Laos’ river section have become operational, while four more have been notified to the MRC for the Prior Consultation Process, according to the MRC.

Altogether with tributary infrastructure projects, the number of hydropower projects in the lower basin as of 2019 stands at 89, with a total installed capacity of 12,285 MW, according to the river governing organization. Of these, two are in Cambodia (401 MW), 65 in Laos (8,033 MW), seven in Thailand (1,245 MW), and 14 in Vietnam (2,607 MW).

14 dams with a total capacity of 3,000 MW were expected to come online during 2016-2020, while 30 others are in the planning stage with the majority finalising feasibility studies. By 2040, hydropower in the basin is estimated to generate more than 30,000 MW, the MRC notes.

I Clockwise: The Pak Mun Dam stands tall on the Mun River, near its mouth in Khong Cthe hiam district of Ubon Ratchathani province, triggering a fierce conflict over water resource development and conservation; The Lower Huai Luang Basin Development project is underway to make optimum use of water in the region; One of the highly controversial dams under the Kong-Chi-Mun mega-project, the Rasi Salai dam. Photos: ©KAS Thailand/Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Their impacts, meanwhile, keep emerging.

After the new dams upstream began to store water in the early 1990s, villagers in the bordering province of Chiang Rai noticed fluctuations and drop in the water levels for some years. These posed hardships to several fishers to maintain their traditional fishing livelihood, not to mention several other occupations that depend on the rivers to the point that they become highly controversial these days.

As noted by the MRC itself: “The UMB-China dam cascade has led to significant increases in dry season flows, considerable reductions of wet season flows, and impacted the sediment budget of the Mekong River system.”

Downstream, the impacts of the dams built and planned downstream are picking up more and more attention from the public. The most notable studies are done by the MRC Council Study, which notes that the Lower Mekong Basin could see economic gains from full hydropower development of more than US$ 160 billion by 2040. But those benefits come with potential costs.

“The decline of fisheries could cost nearly US$ 23 billion by 2040. And the loss of forests, wetlands, and mangroves may cost up to US$ 145 billion. With further reduction of sediment due to dams and sand mining, rice production along the Mekong will be severely curtailed, although fish farms, irrigation schemes, and expanding agriculture could offset these losses with uneven results between countries,” the study notes.

What far lesser known are the impacts on the mainstream’s numerous tributaries and their intricate relationships.

The Mekong tributaries

Dr. Kanokwan, who has conducted social research on rural development in the region for decades, said that the first and foremost thing to understand is the values of these tributaries to the mainstream river. Numerous rivers and tributaries in the Mekong Basin like Mun, Chi, and Songkhram in the Northeast and several more in Laos and elsewhere in the basin are vital to the mainstream river ecosystem as they are areas that accumulate nutrients and fertility to be fed to the ecosystem.

These tributaries flow downstream through a wide range of landscapes from watersheds on high mountains to flat floodplains and wetlands, picking up nutrients, accumulating and exchanging them along the way, and generating sub-ecosystems_the ecological service processes that support riverine species and the entire river system.

“They are areas that help support and maintain the ecological balance of the mainstream river, Without the tributaries, the Mekong River would barely exist,” said Dr. Kanokwan. This is particularly true at the river’s confluences, Dr. Kanokwan said, citing several river mouths where the Mekong River meets its tributaries and become rich in biodiversity to the point that they provide productive nursery grounds for riverine species.

The Mekong tributaries at the same time nurture locals’ way of life and culture, being part of their social and cultural histories, according to Dr. Kanokwan. Following the richness of biodiversity, people have developed their unique way of life and river culture, under which several rituals and social norms and practices are held and help bond river communities along the tributaries, be they Naga (a giant snake) worshipping, Songkran celebrations, and several others.

“This grouping is different from administrative zoning, and people need to bear this kind of connection in mind when they want to introduce or pursue development in the areas. It’s the bond that connects people with their resources and environment and it should be taken into account for sound and sustainable development initiatives,” said Dr. Kanokwan.

I The local residents make a living at the Lower Songkhram River using a variety of fishing gears developed upon their accumulated knowledge and skills about the river and environment. Photos: ©KAS Thailand/Sayan Chuenudomsavad

The Mekong tributaries are also areas where community rights and power are held firm as such. This is because people have accumulated the knowledge and norms to make a living and live with these tributaries for a long time, and they have cemented their power and rights over the resources there, Dr. Kanokwan said.

For instance, to live by the Mun or Songkhram Rivers, people have to learn about the rivers’ resources and environment and how to make use of them at best. Pla Daek (Pla Ra) Culture, or the culture of fish preservation and exchange of local resources among kins and neighbours is a strong instance demonstrating the point, Dr. Kanokwan outpointed.

Nevertheless, such rights and power have been undermined by the state due to the lack of understanding in the locals’ way of life and their resources. Every time the state tries to develop the areas, clashes of power and knowledge over resources management often take place, Dr. Kanokwan said, citing a prominent case of the Kong-Chi-Mun mega project in the Lower Northeast in the early 1990s that has faced strong and years-long protests, ones that marked people’s mass protests against state-run development projects in the country.

“The fact is this kind of power and knowledge is developed upon people’s way of life and the values of their resources, but it is often overlooked by the state. Clashes between the state and the locals often occur as a result. Although there is some room for negotiation in some cases, power is not equal. The question is who should have the right to speak and decide on development introduced to the areas,” said Dr. Kanokwan.

Last but not least, if the tributaries become unsustainable, how would the mainstream Mekong be sustainable? And if the mainstream Mekong becomes unstainable, how would the tributaries become? Dr. Kanokwan asked.

“We really need to look at them and manage them as one whole basin. A crisis elsewhere can send impacts somewhere because the rivers are all connected,” said Dr. Kanokwan.

Unknown territories

While impacts on the mainstream Mekong are extensively reported, what far lesser known are the impacts on the mainstream’s numerous tributaries and their intricate relationships.

Over the past year, Bangkok Tribune had a chance to explore such impacts on the ground as well as relationships of the rivers in Thailand’s Northeast or Isaan, which forms one-third of the Mekong Basin’s population of 60 million people, through the photo essay project called “The Mekong’s Womb”.

Aside from learning about the devastation some development projects have already made to the tributaries like Mun and Chi in the Lower Northeast (Read: The Saga of Mekong Tributary Dams/ Battling odds to revive the ‘Nai Hoy’s way’ amid Rasi Salai upheaval), the news agency has also documented initial changes at the most important Mekong tributary in the Upper Northeast of Thailand; the Songkhram River.

Running over 400 kilometres through the upper Northeastern region, the Songkhram River is the Mekong’s tributary that contributes around 1.8% of the average annual water flows to the Mekong River at Tha Uthen district in Nakhon Phanom province.

Formed geographically as a vast floodplain, approximately 54% of the overall Songkhram Basin, which is the second-largest basin of the Northeast with a total area sized around 6,473 square kilometres or around four million rai, could be classified as “wetlands”. The most extensive area, as noted by the Ramsar Site Information Service, is concentrated in the lowland floodplains of the lower section of the river.

Every year, the Mekong’s backflow specially intrudes this lower section of the river during the peak flooding period from July to late September, prompting a rare phenomenon of “flood pulse” that is reported to travel as far as 300 kilometres inland during some flooding years and flood as large as around 80,000 to 96,000 hectares (500,000 to 600,000 rai). Such a rare and unique phenomenon occurs only in a few places, including the region’s largest lake of Tonle Sap in Cambodia.

According to Ramsar, this “flood pulse” phenomenon contributes to complex water-based geographical characteristics, ranging from permanent and temporary surface water sources, artificial and natural wetland habitats, and a range of riverine, floodplain, lacustrine, palustrine, and salt-water wetlands.

It also significantly contributes to the unique landscape and ecosystem of lowland floodplain forests or locally called Bung-Tham forests, where the flooding lasts longer than in other areas, thus boosting nutrients and biodiversity there and in turn providing productive nursery grounds for the Mekong’s fish.

Sarun Boonprasert, a noted environmentalist and editor of The Mekong’s Womb book, said at the same forum that most of the rivers in the Northeastern region possess a unique meandering character due to the region’s relatively flat landscape.

As a result, floodwaters hardly escape the areas, and this is particularly dominant in the lower section of the Songkhram River, which additionally experiences the backflow from the Mekong. Such a unique phenomenon combined with the relatively flat floodplains creates a vast ecosystem of lowland floodplain forests or locally called Bung-Tham forests hardly found elsewhere.

“In Laos, there is a much larger number of Mekong tributaries, but the landscapes are mostly sloppy, not flat like those in the Isaan region. The Mekong meanwhile is torrential and not suitable for the fish to lay eggs. So, there are really some places like Bung-Tham forests that can provide the Mekong’s fish productive nursery grounds, and that’s the reason why Bung-Tham forests in the Isaan region, especially those in the Lower Songkhram basin are important to the mainstream ecosystem,” said Mr. Sarun.

According to Ramsar, across the lower section of the Songkhram River, at least 232 species of plants can be found, including 55 species of trees, 73 species of shrubs, 26 species of vines, and 38 species of water plants. In the 34,400 rai of Bung-Tham forests in the lower section designated as the country’s 15t Ramsar site in 2020, 192 varieties of fish, which are both residents of the Songkhram River itself and migratory ones from the Mekong River, are recorded.

The Songkhram River basin is also dotted by human settlements for ages. According to the Mekong’s Womb book, there is evidence of denser human settlements in the upper part of the river that could be traced back 3,000-4,000 years to the Ban Chiang Civilisation. Since then settlements have expanded along the river, with up to 120 ancient settlements being recorded along with abundant artefacts.

According to Walailak Songsiri, a sociologist and historian at the Lek-Prapai Viriyaphant Foundation, who has conducted extensive archaeological research in the basin for years, the Songkhram River basin has long been one of the region’s prime human settlements, given rich archaeological artefacts discovered along the river.

Ms. Walailak’s research has shown that the basin’s settlements can be divided into two prime areas; the upper part of the basin and the lower section which is wetter. In some prominent swamp areas, such as Nhong Hthe an swamp in Udon Thani province, human settlements were clearly recorded, reflecting a common characteristic of human settlements in such wetland areas shared in Thailand and Southeast Asia.

Ms. Walailak’s research team unearthed more than 90 ancient kilns believed to be used to produce earthen pots for secondary burials along the mid-section of the river. As the area is subject to stark seasonal change, uses of resources there are also seasonal, she said, citing pottery production and rock salt production as notable cases.

Pots for fish preservation were also discovered downstream especially in fishing villages like Pak Yam, reflecting the importance of the area as an economic zone, she said.

“Based on our studies, we have learned that the basin is very ecologically and sociologically important. Waters are always sources of life and human history and culture, and so are inland water sources of the basin. They help keep water for the people there, feeding their lives and culture far better than any dams or reservoirs,” said Ms. Walailak at the forum. “That’s the reason why we helped fight against several water development projects planned on the Songkhram in the past.”

“Unknown” impacts

In spite of its values, the Songkhram River has been under threat like other basins elsewhere. Ramsar noted that factors influencing the ecosystems at the new Ramsar site on the lower section of the Songkhram include habitat destruction, overexploitation, alien species, chemical pollution, infectious diseases, habitat change and others such as global warming.

Among these threats, it said, those causing the greatest impact are habitat destruction, overexploitation and habitat change. Other threats, it added, have the potential to cause minor or “unknown” impacts.

Ormbun Thipsuna, Secretary-General of the Network Association of the Mekong Community Organizations Council of the Seven Northeastern Provinces, who shared the people’s experiences on the panel, said people in the seven “Mekong provinces” in the Northeast have experienced an unusual change in the mainstream Mekong clearly in recent years although they are still in the dark which dams are the real causes of the impacts downstream.

“The river has become unpredictable. It does not follow the seasons. It’s not dry when it’s supposed to be dry, and it’s dry during the wet season instead,” said Ms. Ormbun. “Fish get lost, and so do the fishers. I’m just wondering how long they and people’s livelihlivelihoodslast. The knowledge about the river and the fish that people there have seems to become incompatible with this changing environment.”

At Songkhram, “the flood pulse” is disappearing. Ms. Ormbun said the residents there saw the last flood pulse around four years ago, or in 2018.

“The Mekong’s womb is wilting and cannot be as productive as it used to be,” said Ms. Ormbun.

The local residents make a living the in wetlands and Bung-Tham forests of the Lower Songkhram River. Some do not notice the changes, while others have started feeling the pinch. Photos: ©KAS Thailand/Sayan Chuenudomsavad

Yanyong Sricharoen, Lower Songkram River Management Project Manager and Head of Fresh Water Conservation for WWF-Thailand, said at the forum that the Songkhram River is increasingly sharing the same fate as other tributaries, from Chiang Rai to the Lower Northeast, as they are all connected to the same Mekong.

Based on WWF, which helped prepare the proposal for nominating the Lower Songkhram section as a Ramsar site, the ecosystems at the Songkrham River have changed a lot compared to the past 15 years when the organization started its work there.

The WWF working group, which has been working on the ground there, reported that the river especially its lower section has been increasingly facing various threats in recent years. These include large-scale water resources development projects on the river itself, which have added further complications to the flow regime of the river.

The working group reported that the local residents had felt the changes in the river section and raised questions about the dams on the Mekong, both in Laos and in China. They suspected that these dams are the main reason for the unusual absence of Mekong’s backflow and flood pulses last year.

They were also concerned about new development projects which are being pushed in the area, including the construction of sluice gates at the river’s mouth and in the middle part of the river.

According to the Office of National Water Resources (ONWR), it has come up with an integrated water development plan to address what it claims are chronic issues in the basin: floods and drought.

Planned projects include the construction of large sluice gates at the mouth of the Songkhram River, the middle of the river, and upstream to help regulate the flows of the river itself and the Mekong River. In total, up to 1,644 structural and non-structural water management projects have been planned for both short-term and long-term periods (20 years) for the Songkhram River Basin. Among the top priorities are the two sluice gates on the Lower Songkhram.

“Since the rivers become more and more unpredictable, the state has expressed its intention to fix the problem too but we at WWF and the residents there are concerned about the adverse impacts if those structures are built on the river. What we are trying to do at best is learning the lessons from other basins including the Mun and Chi basins for the residents to have enough information to make a decision one day,” said Mr. Yanyong.

Cultural Ecology, the missing piece

ONWR’s director of the River Basin Management Division Patcharawee Suwannik told the audience that the state has recognized the increasing threat in the basin and come up with the new water resources management act to allow more room for integration and participation from all stakeholders.

One of the key elements to help enforce the act is the new water resources organisations and basin committees at various levels that will act as platforms for joint discussion and decision-making. The lowest level would be water users organisations, under which at least 30 water users in the same area register as an independent grouping. They then will be endorsed so that they can take part in the processes, according to Ms. Patcharawee.

The Songkhram River Basin will be managed under the same processes and structures, she said, insisting that all plans and projects to be developed and put in place for the basin will be passed through these the same way as other basins, thus actual participation is promoted.

The experts questioned, nevertheless.

They said what lacks in the state processes is an understanding of the nature of the rivers and the people who live with them. Water, they said, is not just a substance to be managed. It’s full of resources, ecosystems, livelihoods, as well as dependent relationships between them, something they call “Cultural Ecology”.

“Water is not about flood and drought. It’s about fish, rock salt, earthen pots, plants, people’s rituals and leisure, and several others that are often missed to be taken into account when it comes to development. The state often looks at the water with a narrow perspective, while in fact, it needs a holistic view to understand it and the contexts around.

“It’s time for us to look at it in a holistic manner. Otherwise, our rivers will be chopped into pieces like this because we want to regulate “the substance”. The rights of our rivers should be promoted and endorsed like the Ganges or Yamuna, so that we can see them as the “living entities”, treating them and living with them with respect and holistic views,” said Ms. Ormbun.

To start with, “see” and listen to the people, suggested Dr. Kanokwan.

“Put the ecosystems and cultural ecology upfront, not the bodies of water. Only this you can see the whole picture of the river basins that will help guide you to strike the right balance,” said Dr. Kanokwan, suggesting applying the Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) as a tool for future sustainable planning for the river basins.

The recent forum, The Songkhram River Basin, the Mekong’s Womb, organised by Bangkok Tribune and its alliances in support of Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. Foundation Office Thailand (KAS Thailand), BACC, and Thai PBS. Photos courtesy of Thai PBS

Also watch: FB LIVE RECORDING I The Special Forum: ลุ่มน้ำสงคราม (The Songkhram River Basin), the Mekong’s Womb

Also read: ลำน้ำสาขา …คือสายเลือดที่หล่อเลี้ยง

Indie • in-depth online news agency

to “bridge the gap” and “connect the dots” with critical and constructive minds on development and environmental policies in Thailand and the Mekong region; to deliver meaningful messages and create the big picture critical to public understanding and decision-making, thus truly being the public’s critical voice